The Miami Erie Canal was a huge deal. It revolutionized trade between Butler County and the l arge cities on the east coast.

The Miami-Erie Canal was 248 miles long, 40 feet wide and 4 feet deep with 10-foot towpaths on each side. There were 19 aqueducts, which were wood bridges carrying the canal over lower streams and valleys to prevent water loss.

The system had 103 locks, an average of one every 2.4 miles. The lifting and lowering devices were necessary because Lake Erie is 117 higher above the Ohio River. St. Mary’s lake was built as a reservoir for the canal.

Ohio’s canal system was most effective fir a relatively short time between 1827 and 1855 before the railroads became prominent for trade.

The first railroad was completed into Hamilton in 1851. By the late 1860s — immediately after the Civil War — the canal system was in rapid decline.

The 1913 Flood destroyed much of the canal.

The Canal was finally filled-in in 1935.

The Miami-Erie Canal was 248 miles long, 40 feet wide and 4 feet deep with 10-foot towpaths on each side. There were 19 aqueducts, which were wood bridges carrying the canal over lower streams and valleys to prevent water loss.

The system had 103 locks, an average of one every 2.4 miles. The lifting and lowering devices were necessary because Lake Erie is 117 higher above the Ohio River. St. Mary’s lake was built as a reservoir for the canal.

Ohio’s canal system was most effective fir a relatively short time between 1827 and 1855 before the railroads became prominent for trade.

The first railroad was completed into Hamilton in 1851. By the late 1860s — immediately after the Civil War — the canal system was in rapid decline.

The 1913 Flood destroyed much of the canal.

The Canal was finally filled-in in 1935.

Identified by the Cummins Collection as the lower canal locks of the Miami-Erie Canal at Dayton Street, Hamilton, Ohio, ca. 1892. Appears to be the lock referred to by William Dean Howells in his novel “A Boys Town” as the “First Lock.” From the George C. Cummins “Remember When” Photograph Collection. Donated by the family of George C. Cummins. Photo used courtesy of the George C. Cummins "Remember When" Collection at the Hamilton Lane Library, Hamilton, Ohio.

In-depth - The Canal...

The canal era was relatively brief here, but it brought many changes to Butler County. Despite its speed limit of 4 miles an hour, the waterway was the region's most efficient form of transportation in the 1830-1855 period.

Ceremonies starting the Miami-Erie Canal were held July 21, 1825, south of Middletown. A marker is at the spot, now the northeast corner of Verity Parkway and Yankee Road.

The Middletown rites weren't the first in Ohio. Seventeen days earlier — July 4, 1825 — ground was broken at Licking Summit, near Newark, for the 308-mile Ohio-Erie Canal between Cleveland on Lake Erie and Portsmouth on the Ohio River.

That event was exactly eight years after the July 4. 1817, start of New York's Erie Canal.

The 363-mile Erie Canal — linking Albany on the Hudson River and Buffalo on Lake Erie — was called "Clinton's Ditch" after its staunchest advocate, Gov. DeWitt Clinton.

The New York project infected Ohio with "Canal Fever," and Gov. Clinton had top billing when he joined Gov. Jeremiah Morrow and other notables at the Newark and Middletown ceremonies.

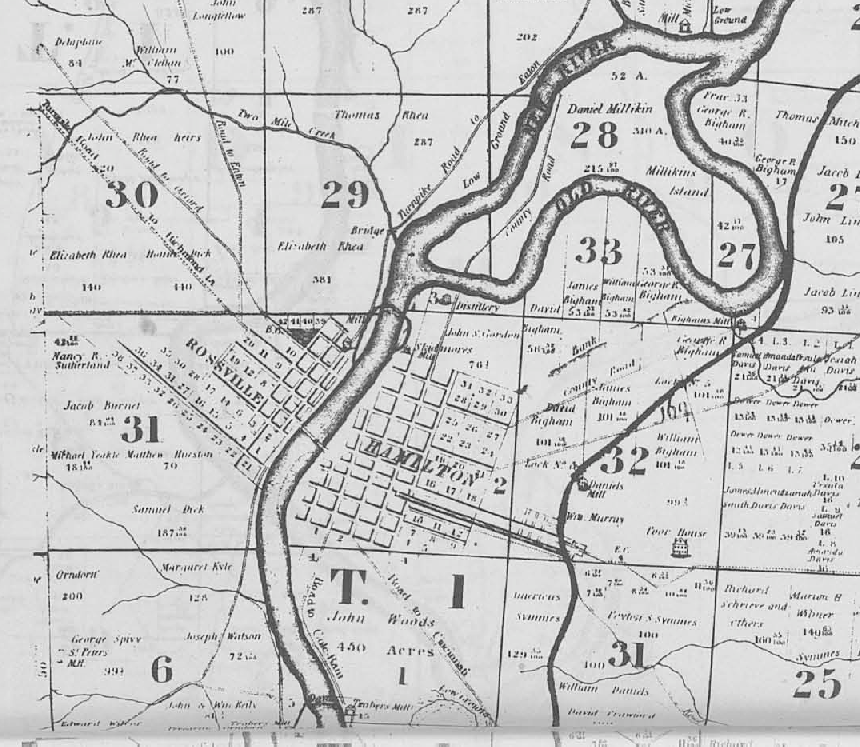

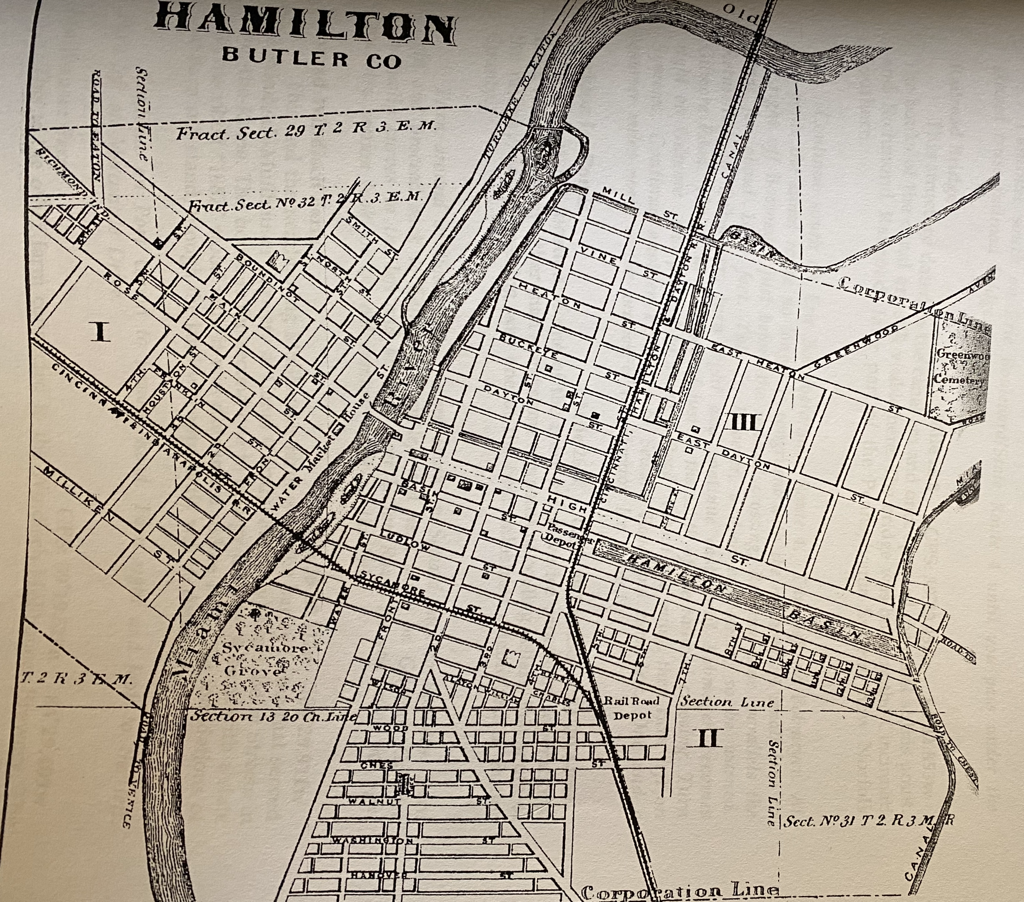

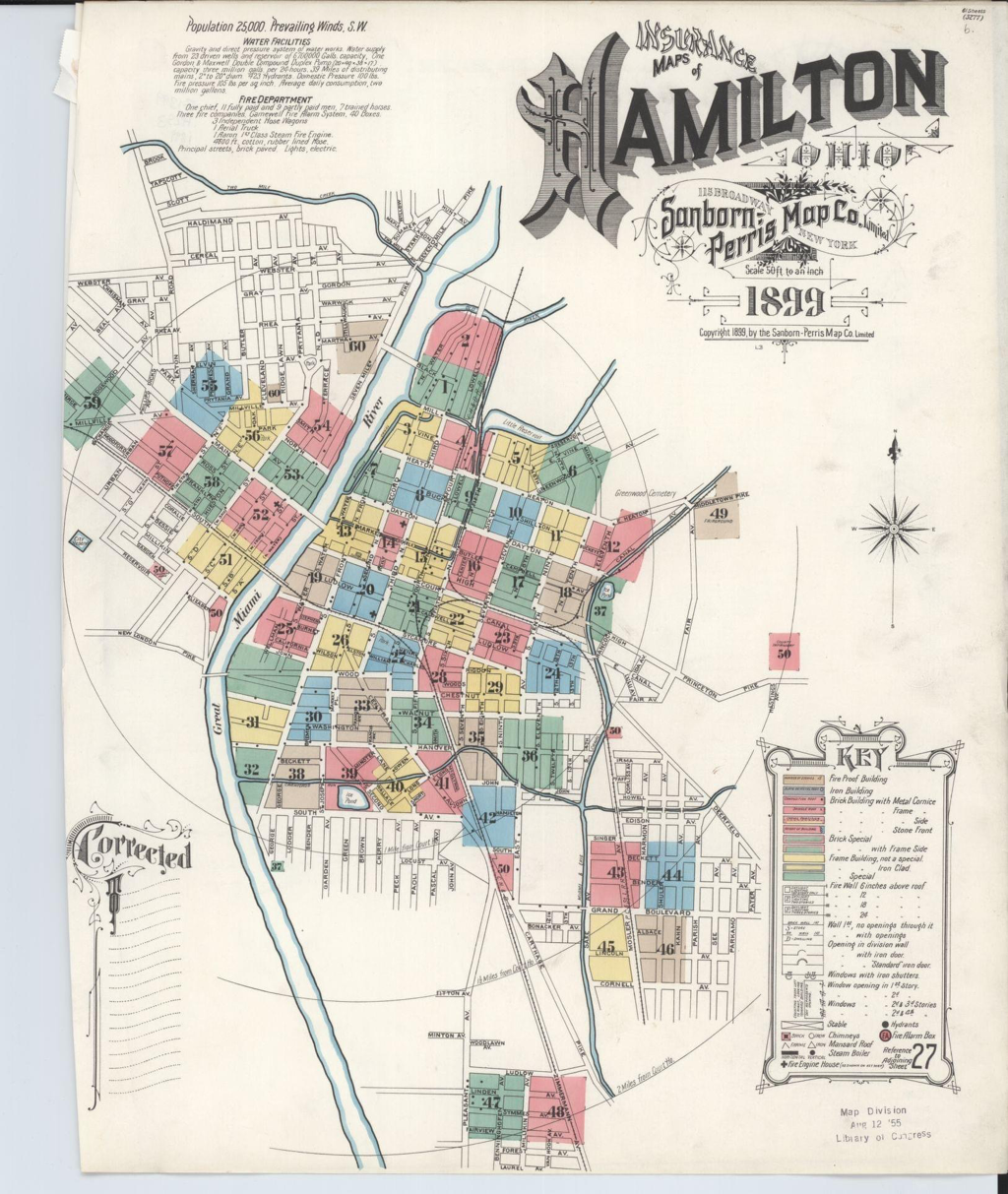

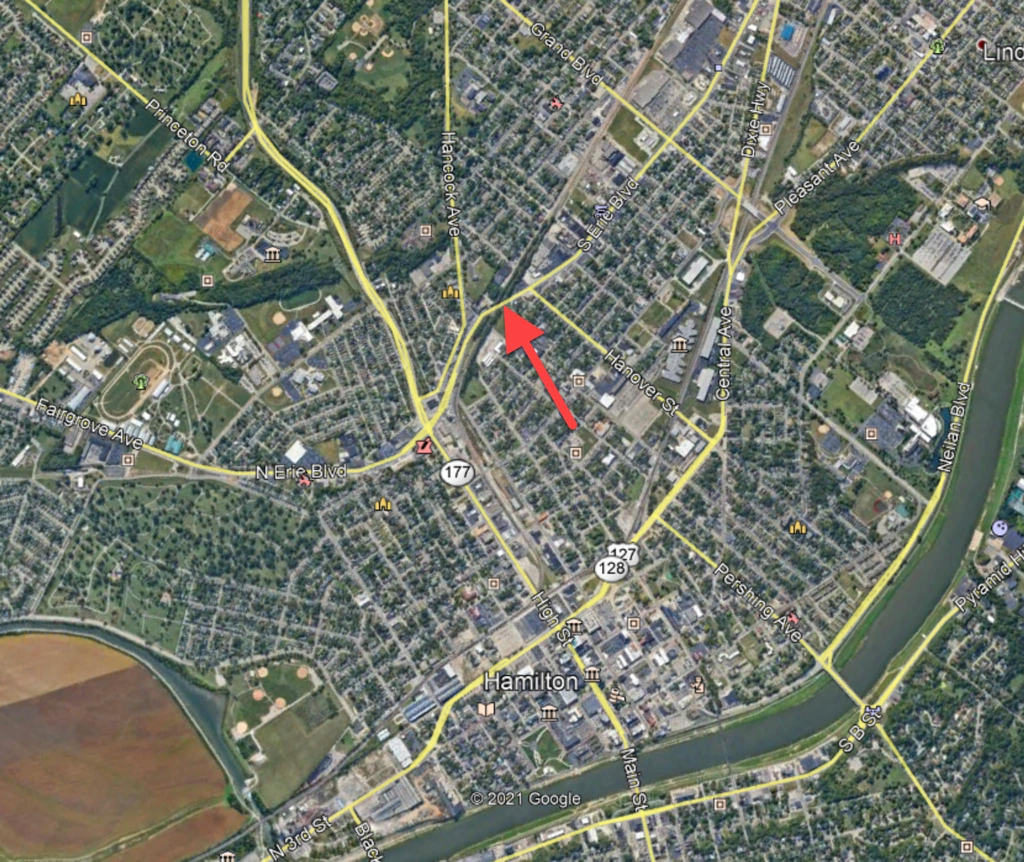

Eventually, the 248-mile Miami-Erie Canal ran between Cincinnati on the Ohio River and Toledo on Lake Erie — coursing through Lockland, Hamilton. Middletown, Franklin, Miamisburg, West Carrollton, Dayton, Tipp City, Troy, Piqua, St. Marys, Delphos and Napoleon.

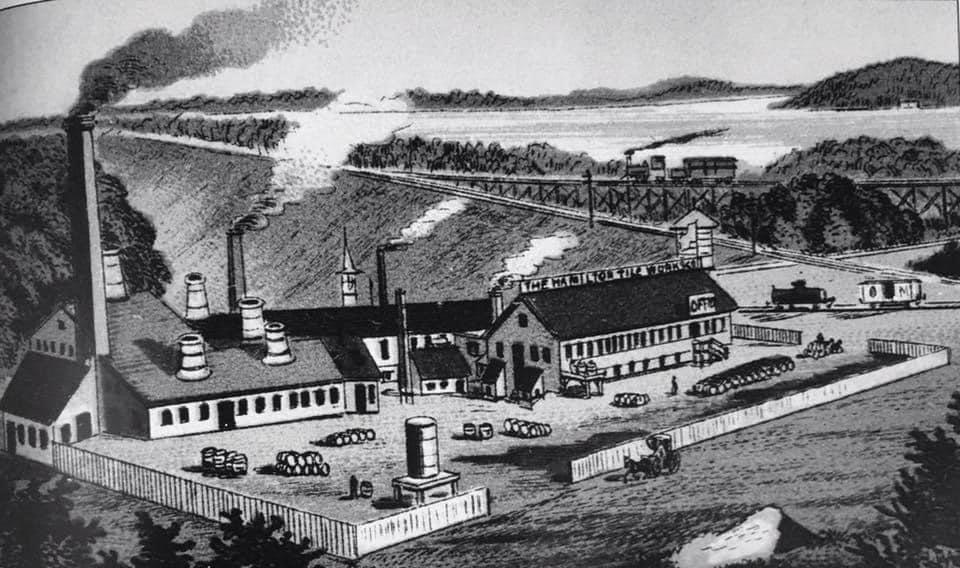

Butler County was the first to feel the economic and social impact of the Miami-Erie Canal, which originated as the 67-mile Miami Canal between Dayton and Cincinnati.

For engineering and political reasons, state canal leaders began by first building the 44-mile section from Middletown south to Cincinnati.

This was a flat stretch that required few locks to raise and lower boats about eight feet.

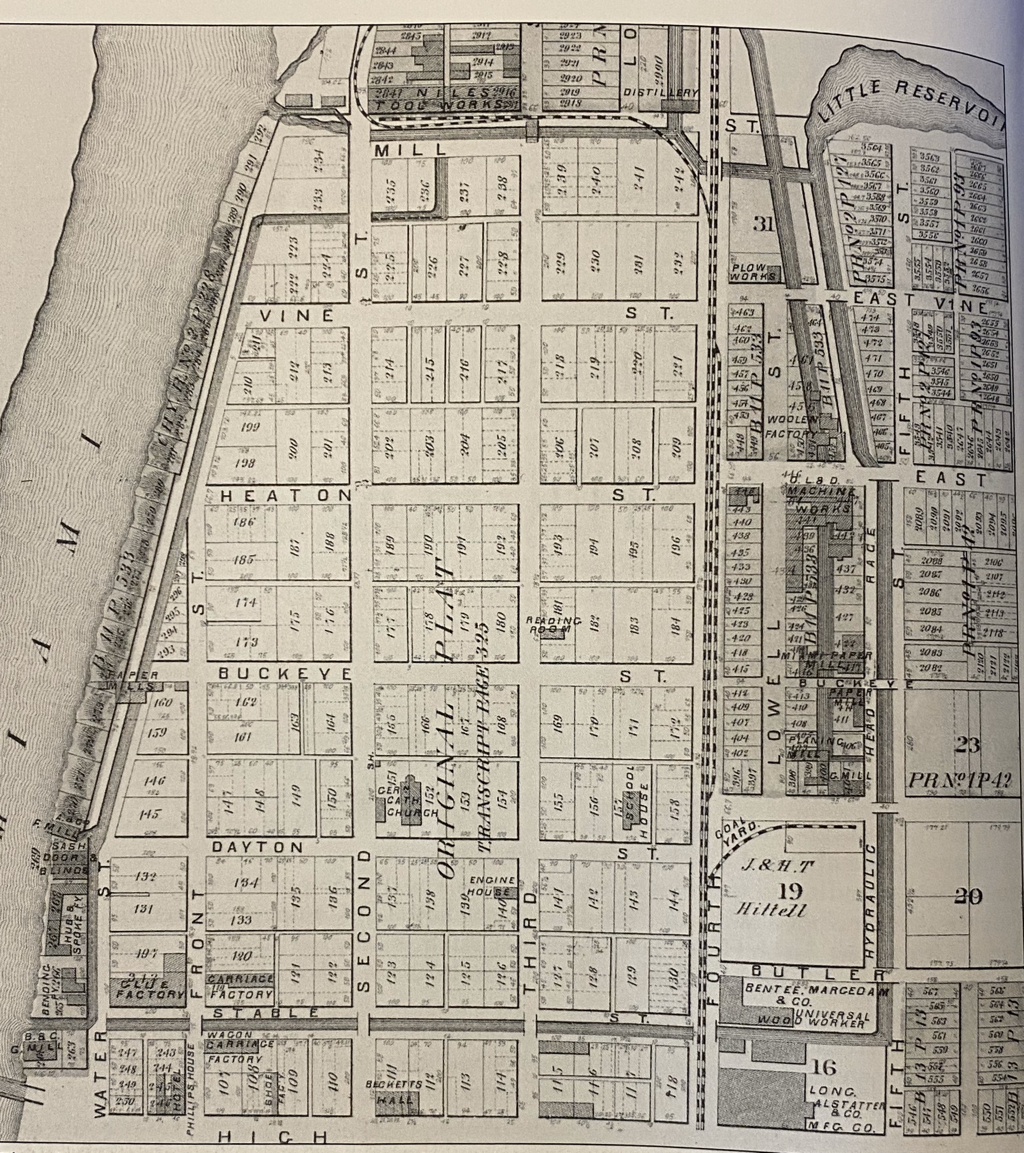

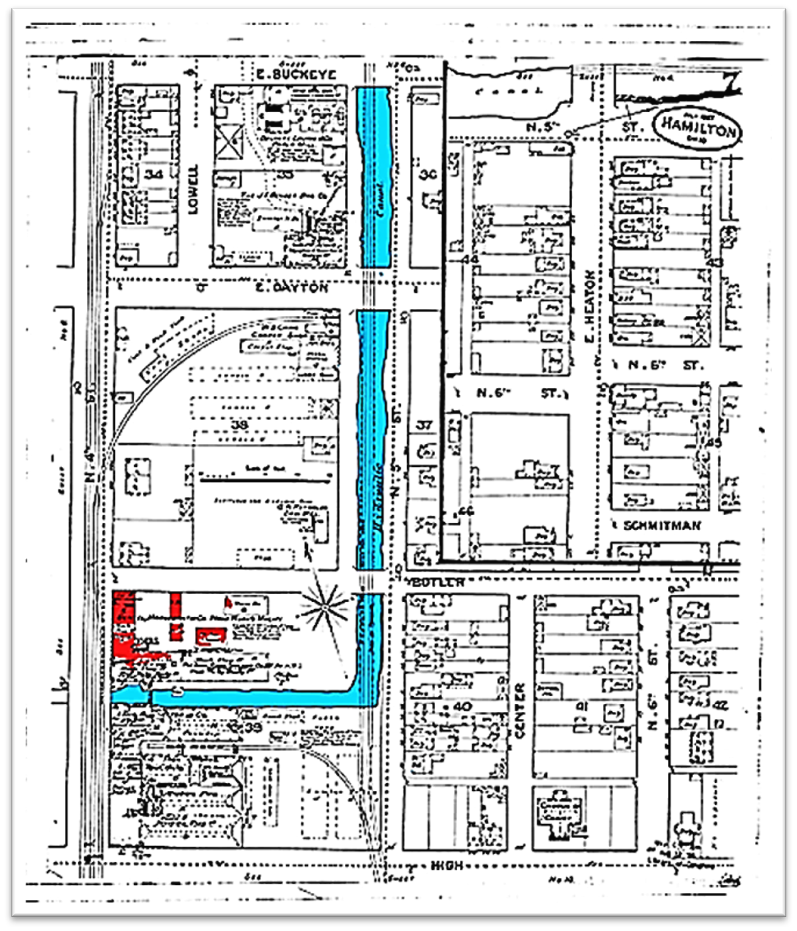

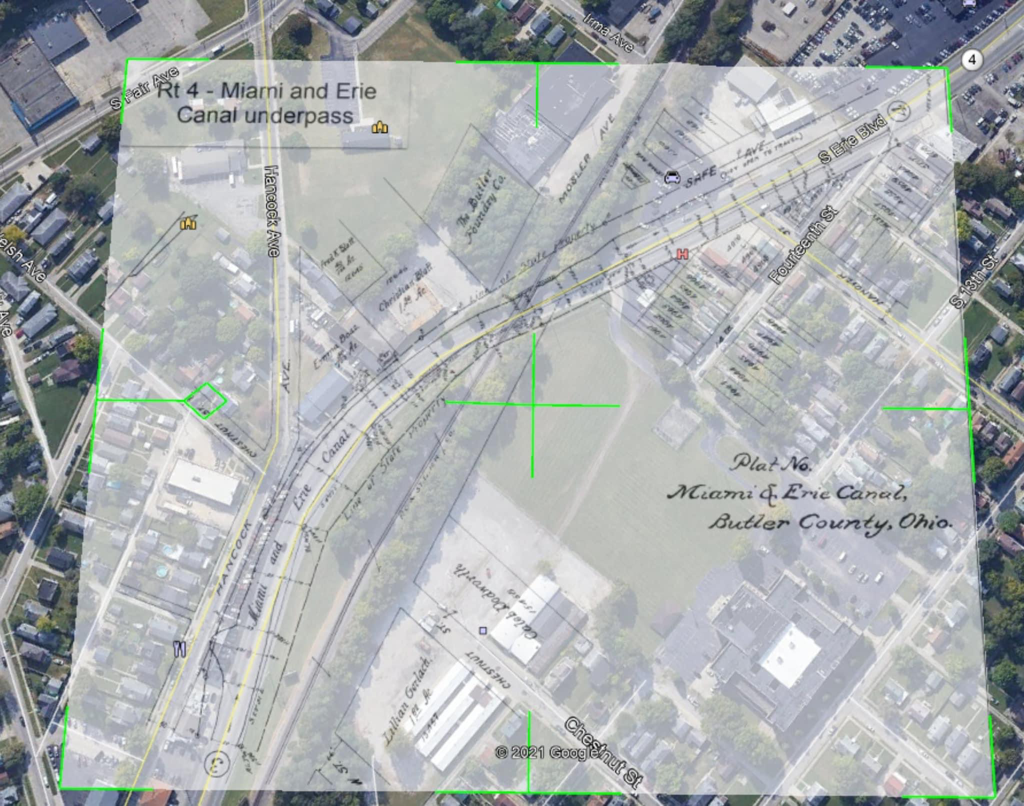

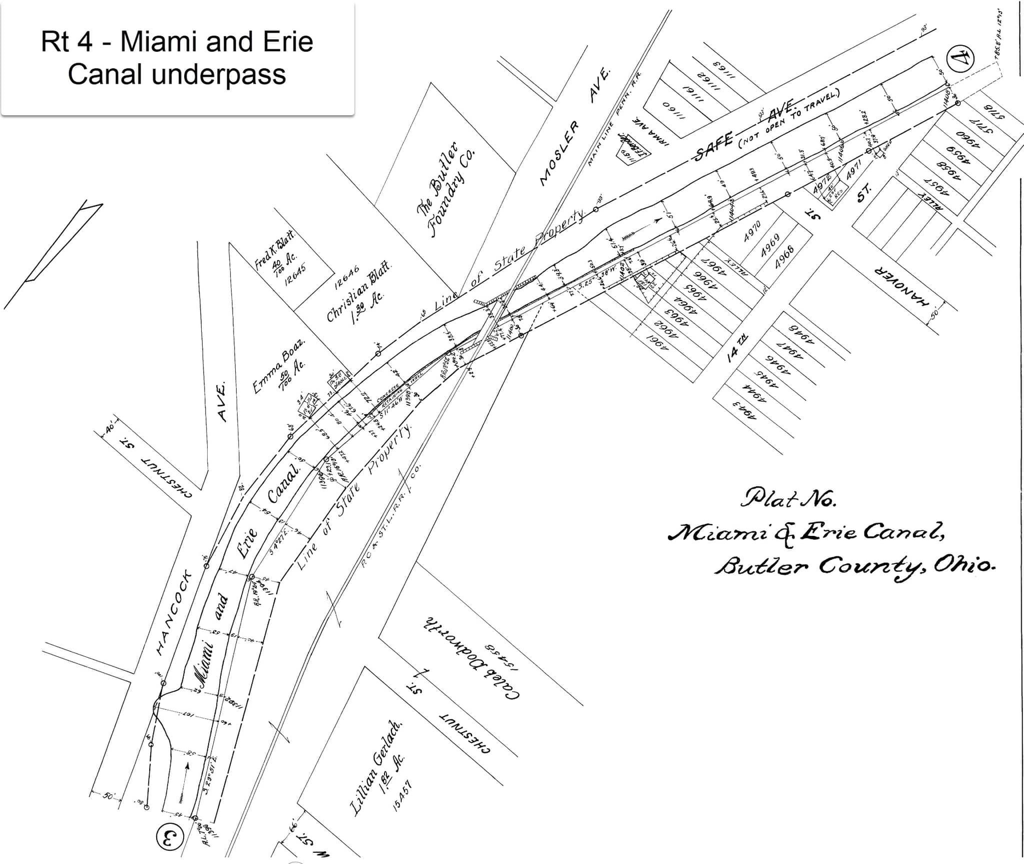

For example, it was five miles between a lock north of Dayton Street in Hamilton and the next lock at Port Union in southeast Butler County. This economical section was called the "Five Mile Level."

By September 1825, about 1,000 men. mostly local farmers and their sons, were working on the canal in Butler County. They labored with pick, ax. spade and wheelbarrow for 30 cents a day. A farmer supplementing his muscle with his horse or ox was paid 75 cents a day.

Each canal laborer also received a jigger of whiskey each day to prevent malaria, which caused about one death for every three miles of canal in Ohio.

They built a waterway 40 feet wide and 4 feet deep with 10-foot towpaths on each side.

The 15-mile segment from Middletown to a point east of Hamilton was completed in August 1827. It reached south to Cincinnati in December 1828 and north to Dayton in January 1829.

The cost of building the first 67 miles, which included 32 locks and six aqueducts, was about $900,000.

The northern extension from Dayton to Toledo wasn't started until 1837 and was completed in 1845, running Ohio's bill for the full 248 miles of canal to more than $8 million.

Three reservoirs — With Grand Reservoir between Celina and St. Marys being the largest — were built to maintain a steady supply of water for the Miami-Erie Canal.

There were 19 aqueducts, which were wood bridges carrying the canal over lower streams and valleys to prevent water loss.

The system had 103 locks, an average of one every 2.4 miles. The lifting and lowering devices were necessary because Lake Erie is 117 higher above the Ohio River.

The highest point on the Miami-Erie at Loramie is 512 feet above the Ohio River. That required a northbound canalboat to be raised the equivalent of a 50-story building in about 100 miles. The Carew Tower in Cincinnati is 49 stories.

The Butler County farmers were more interested in income than canal engineering.

A state study in 1822 said flour, which sold at $3.50 a barrel in Cincinnati, would bring $8 in New York. It would cost $1.70 to haul that barrel to New York via canals, leaving the Ohio farmer an additional $2.80 in profit.

The canal was almost rebuilt in 1932, but the Army Corp of Engineers declined.

Not everyone welcomed the September 1851 opening of the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton Railroad that brought the first rail services to the latter two cities in its name. Those unhappy with the event included patrons and operators of the Miami-Erie Canal, a transportation system that had connected the same cities for more than 20 years.

The canal -- built by the state -- had carried passengers and freight between Cincinnati and Hamilton on a seven-hour schedule. The privately-financed CH&D did it in an hour or less.

Statewide, a canal report said, railroads in 1852 took advantage of a loophole in a new Ohio law, offering lower rates to shippers at places where the two competed. The statute mandated uniform railroad freight rates, but "no penalty is provided for the violation of its provisions," canal managers explained.

A canal official said the CH&D was determined "to monopolize the carrying trade between these points" (Cincinnati, Hamilton and Dayton).

"We deemed it our duty to do all in our power, not only to sustain those who had made large investments in warehouses and boats on the canal, but also to protect the revenues of the state," said a state report for 1852 operations.

Weather affected both systems, but in the first full year of head-to-head competition, the southern half of the 249-mile Miami-Erie Canal suffered the most.

Dec. 14, 1851, ice forced a 17-day closing of the frozen section between Cincinnati and St. Marys. The 95-mile Cincinnati-Piqua portion froze again Jan. 11, 1852, stopping traffic for 25 days.

There was a 10-day closure on the Cincinnati-St. Marys section after March 10, 1852, so repairs could be completed on that segment.

The canal was closed for seven days, starting April 14, because an embankment washed out after the unauthorized installation of a pipe in Cincinnati.

A breach in the levee at Camp Washington near Cincinnati June 14 resulted in a three-day interruption. A leak Sept. 7 at Cincinnati brought another closure.

On the southern half of the Miami-Erie, the report said, "navigation was suspended 10 days by breakage, by ice 42 days and by cleaning and repairing 10 days, in all 62 days. The mills and manufacturing establishments in the city of Cincinnati were deprived of water 20 days only during the entire year."

During some of the 1852 shutdowns, canal directors completed improvements.

"On the six-mile level north of the town of Hamilton," the report said, "was built an extensive waste gate and culvert combined. This culvert was erected for the purpose of passing the water of a small branch or run under the canal, which before passed into it, causing at every freshet a large amount of earth, gravel and stone to be deposited in the canal, greatly to the detriment of navigation."

Work also started that year on building a replacement dam north of Middletown.

Of the $215,078 spent that year to operate and maintain the canal's southern division, more than half, $128,244, went to repairs.

Statewide, the Board of Public Works reported canal revenues in 1852 totaled $688,775, a drop of $167,577 from 1851, the peak year. That amount represented a 19.6 percent setback.

On the entire length of the Miami-Erie Canal, income dipped from $357,494.25 to $329,529.24 -- a decrease of $27,965.01, or 7.8 percent.

Comparison of 1851 and 1852 canal collections by cities on the CH&D showed the following declines: Cincinnati from $71,504 to $51,596; Hamilton from $6,377 to $3,611; and Dayton from $37,671 to $34,964. Annual canal income the three cities went down $25,381, or 22 percent -- from $115,552 in 1851 to $90,171 a year later.

The canal continued in use for several decades, but it never regained the prosperity it achieved before the arrival of railroads in western Ohio.

The Electric Mule

773. Jan. 15, 2003 -- Electric mule failed to revive canal:

Journal-News, Wednesday, Jan. 15, 2003

Electric mule failed to revive canal business

By Jim Blount

The last of periodic attempts to revive the Miami-Erie Canal through Butler County was launched in 1901 when the state authorized the use of "electric mules" for power on the waterway between Cincinnati and Dayton.

The 249-mile canal -- which linked Cincinnati on the Ohio River and Toledo on Lake Erie -- had opened in 1827 from Middletown and Hamilton to Cincinnati. The state-owned system prospered until railroads siphoned off business in the 1850s. In 1851, its peak year, about 400 boats were running on the Miami-Erie Canal.

The state, after spending millions on construction and maintenance, stopped operating the canal in 1877. Some sections, including mileage in Butler County, remained open on a limited basis.

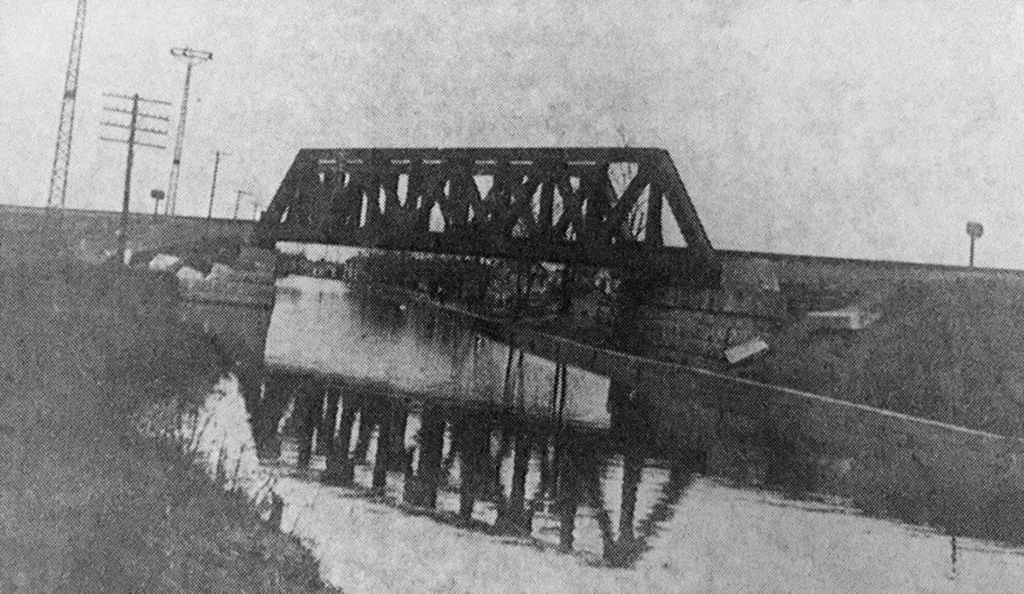

Until 1902, boats in this area were pulled exclusively by mules and horses walking along towpaths at no more than four miles an hour, the speed limit established by the state. In 1901, the privately-owned Miami & Erie Canal Transportation Company (M&ECTC) began installing the "electric mule" system. Electric-powered locomotives or engines, each weighing about 20 to 30 tons, would replace four-legged power.

The improvement required laying tracks along the towpath and erecting utility poles and trolley lines overhead to transmit the electricity purchased from Cincinnati Edison Co. Also, lighting was installed to encourage night passenger and freight service.

In February 1901, to support the private effort, the state began repairing embankments and dredging the right-of-way to a depth of five feet between Dayton and Cincinnati. But the ambitious plan ran into several obstacles and legal hurdles.

In March 1902 the City of Middletown filed an injunction against the company because it had failed to apply to the city for permission to construct track, poles and wire.

Railroads and electric-powered interurban companies opposed the scheme, believing the M&ECTC would eventually abandon the waterway and use the towpath tracks to establish rival rail service. South of Middletown, for example, the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton Railroad never allowed the M&ECTC to cross its tracks. The CH&D created a physical obstacle by stationing a locomotive, caboose and crew at the proposed crossing point.

In April 1902, the company announced its first electric mule had completed a trip between Hamilton and Port Union. An engine pulled six boats loaded with materials for men working on the line. (Since the canal had been built in the 1820s, the segment between Hamilton and Port Union had been known as the "Five Mile Level" because there were no locks in that stretch.)

In October 1902, the M&ECTC was still struggling to complete construction, but the delay didn't discourage the company's general manager.

"More freight is offered us than we can handle, and we have now contracted for every pound of freight that our boats can transport this fall," the GM told a Hamilton reporter. "We will work 40 or 50 boats, too, and will enlarge the fleet as fast as necessary and as fast as we can build the boats."

He also said that "our rates will not be much lower, if any, than those of the railroads, but we believe that by saving the manufacturers along the canal cartage, we will enable them to effect a great saving, enough to make it worth their while to patronize us."

"Our boats will not make the maximum of four miles an hour, which we are permitted to make under the charter, until we are thoroughly acquainted with the conditions we must work under," he said. "In any case, we will not haul them fast enough to wash the banks."

But the project faced too many obstacles. Its northern terminus was just south of Middletown and on the southern end, it never extended into Cincinnati. The canal revival officially ended May 3, 1905, when the electric mule plan was abandoned, leaving debts topping $2 million.

Nov. 20, 1912, a Hamilton newspaper reported "a large number of workmen have been busy during the past few days tearing up the tracks of the old electric mule along the Miami-Erie Canal."