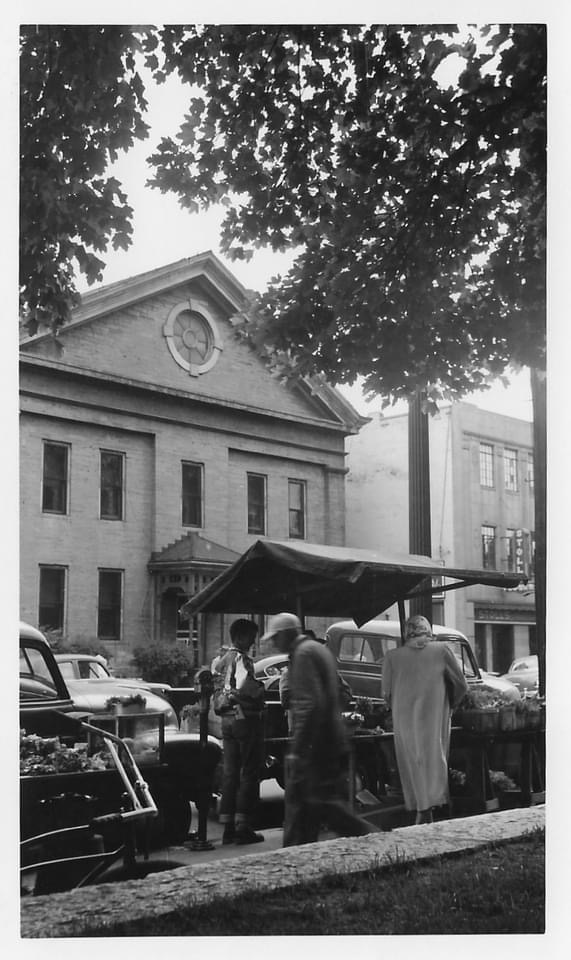

Farmers Market

"Market day was a high day in the Boy’s Town, and it would be hard to say whether it was more so in summer than winter," recalled William Dean Howells in A Boy’s Town, an 1890 book about his boyhood in Hamilton. The noted writer and editor experienced the market in the 1840s between the formative ages of 3 and 11.

The origin of the Hamilton market is uncertain. It goes back to at least 1817. This is the second year that Historic Hamilton, in cooperation with the City of Hamilton, is encouraging patronage of the colorful tradition.

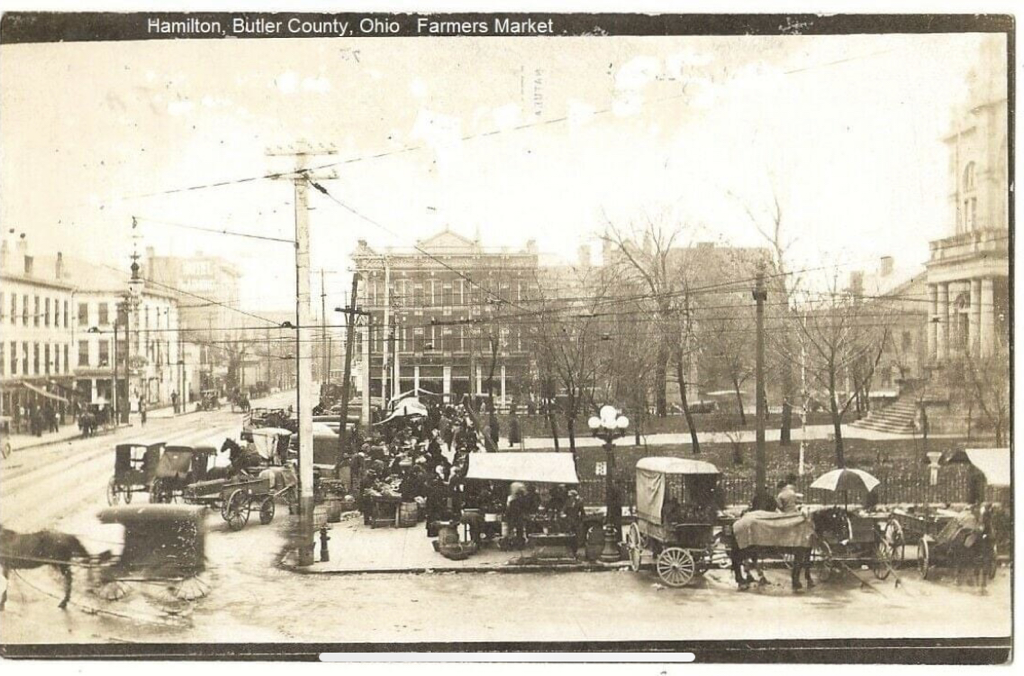

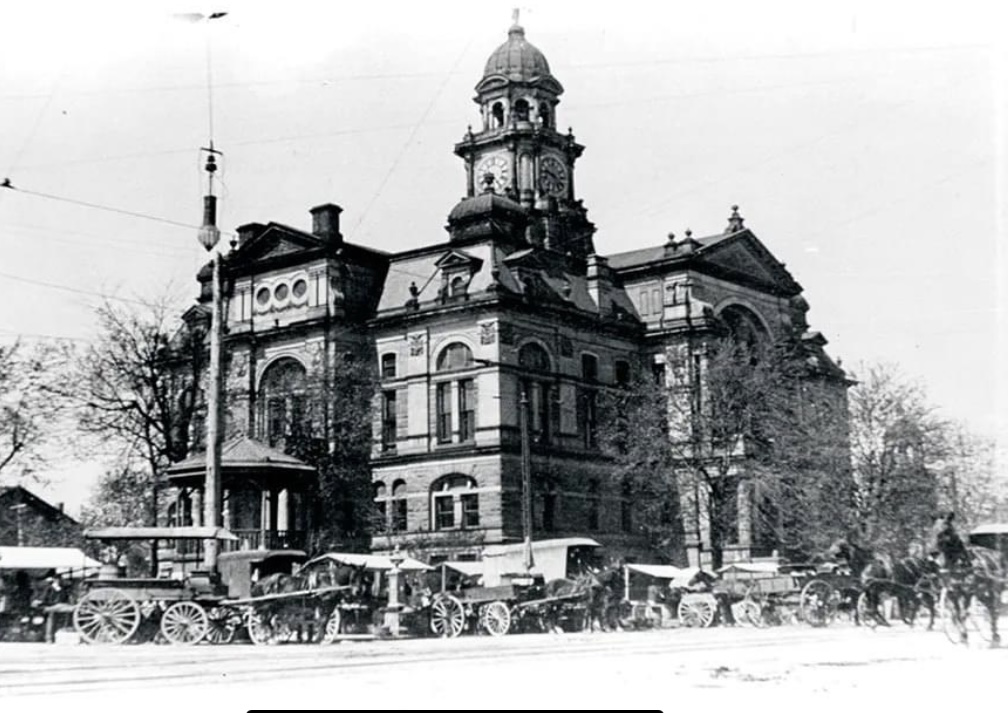

One of his vivid market memories, Howells said, was "the lines of wagons that stretched sometimes from the bridge to the courthouse" as Butler County farmers brought their offerings to downtown Hamilton.

"In summer, the market opened about 4 or 5 o’clock in the morning, and by this hour my boy’s father was off twice a week with his market basket on his arm.

"All the people did their marketing in the same way; but it was a surprise for my boy, when he became old enough to go once with his father, to find the other boys’ fathers at market, too," he said.

"The market house, where the German butchers in their white aprons were standing behind their meat blocks, was lit up with candles in sconces that shone upon festoons of sausage and cuts of steak dangling from the hooks behind them."

"There was a market master, who rang a bell to open the market, and if anybody bought or sold anything before the tap of that bell, he would be fined." According to Howells, the smart shopper arrived well before the bell would ring.

"People would walk along the line of wagons, where butter and eggs, apples and peaches and melons, were piled up inside near the tailboards, and stop where they saw something they wanted, and stand near so as to lay hands on it the moment the bell rang," he wrote.

Howells remembered his father waiting for the bell at a wagon "of some nice old Quaker ladies." He surmised that "they probably had an understanding with him (his father) about the rolls of fragrant butter which he instantly lifted into his basket. But if you came long after the bell rang, you had to take what you could get."

"There was a smell of cantaloupes in the air along the line of wagons that morning, and so it must have been towards the end of the summer," said Howells, a prolific writer recognized in his time as "the dean of American letters."

"After the nights began to lengthen and to be too cold for the farmers to sleep in their wagons, as they did in summer on the market eves, the market time was changed to midday."

Howells recalled "the great heaps of apples and cabbages, and potatoes and turnips, and all the other fruits and vegetables which abounded in that fertile country. There was a great variety of poultry for sale, and from time to time the air would be startled with the clamor of fowls transferred from the coops where they had been softly err-crring in soliloquy to the hand of a purchaser who walked off with them and patiently waited for their well-grounded alarm to die away."

The market master’s authority wasn’t limited to sounding the starting bell, according to Howells, the author of hundreds of books, poems, short stories and articles.

"All the time the market master was making his rounds," he wrote, "and if he saw a pound of roll butter that he thought was under weight, he would weigh it . . . and if it was too light, he would seize it."

Howells was born March 1, 1837, in Martin's Ferry, Ohio. His family resided in Hamilton from 1840 through 1848, while his father edited a weekly newspaper.

Farmers Market

The farmers market started in 1820. The location of the market moved around over the years but was moved to the courthouse in 1855. Market Street was named because the market was moved there in 1910, but that location was unpopular and in 1912 the market moved back to the courthouse.