Prohibition

Prohibition started in Hamilton on Saturday May 24, 1919, and lasted 14 years. All but one on Hamilton’s saloons closed that day. One saloon bought a very expensive state license to stay open one extra day. Eleven grocery stores started selling home brew kits as it was legal to make and consume alcohol in your own home. The Martin Mason Brewery started making “near beer”.

The Lyman Williams Saloon at south Fifth and Henry Streets stayed open one extra day. Look how fancy!

More in depth...

Prohibition came "peacefully and quietly" to Hamilton 70 years ago this month, starting a 14-year ban on the sale, manufacture shipment and consumption of alcoholic beverages.

"The advent of prohibition . . . cast a gloomy shadow over all the bars in the city, which were lined with 'wets' from two in four deep from early evening to the last stroke of midnight, which sounded the death knell of the once happy meeting places, said a news account of the momentous evening.

Enforcement of Ohio's prohibition law began at midnight Monday, May 26, 1919.

National laws restricting the trade in beer, whiskey and wine were effective five weeks later — July 1, 1919. They were imposed by Congress to conserve food during World War I.

The 18th Amendment to the U. S. Constitution — which was believed to establish "permanent prohibition" — took effect about eight months later, Jan. 16, 1920.

Prohibition's immediate cost here would be $111,700 a year. County Auditor Quincy Davis said that was the amount the county, cities and townships would lose from the sale of liquor licenses.

Actually, legal liquor sales ended Saturday night, May 24, in all but one of Hamilton's 58 saloons. That was because state licenses expired the next day, May 25, and Sunday sales weren't permitted in Ohio in 1919.

The entire Hamilton police department was on duty that Saturday night because city officials feared "an unusual amount of disorder" as bar owners tried to sell out stock. Chief Charles G. Stricker posted officers at some of the expected trouble spots.

The show of force apparently worked as a newspaper reported that "prohibition was peacefully and quietly ushered in" here.

"When midnight struck, the lights over the bars were dimmed -- which was the usual signal that leaving time had approached — all turned toward the door, glancing back with a sigh for the last time at the wet bars." the newspaper said. "Fleeting thoughts of the sight of coming soft drink and near beer bars only added to their depression."

The reporter also noted that "celebrators in many places bid farewell to John Barleycorn in song," including versions of "How Dry I Am," "Good Night. Ladies" and "Hail, Hail, the Gang's All Here."

One Hamilton saloon owner paid $305 for a one-day state license so he could operate until midnight Monday. May 26. Lyman Williams' cafe was at South Fifth and Henry streets across from the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton Railroad depot.

Williams bar was enlarged for that one day and pool tables were removed from a back room to allow more space for those seeking "a last chance to quench their thirsts." Six patrolmen also were assigned to the bar at 433 South Fifth Street.

A week later Hamilton police reported no drinking arrests as the community survived its first dry weekend.

In fact, during the first week of prohibition, police arrested only one person and a newspaper said he "came from dry Indiana and brought his booze with him."

Within a few days, former Hamilton saloons were converted into an assortment of new businesses, including pool rooms, hardware stores, jewelry stores and a dress shop.

The Martin Mason Brewery (on South C Street near Millikin Street) advertised its near beer as having "the old-time taste, the old-time color" and "makes the old-time smile."

Eleven Hamilton grocery stores advertised the ingredients for making "home brew" at 25 cents a gallon, Home-brewed beer -- provided it was consumed only by family members — was legal under prohibition laws.

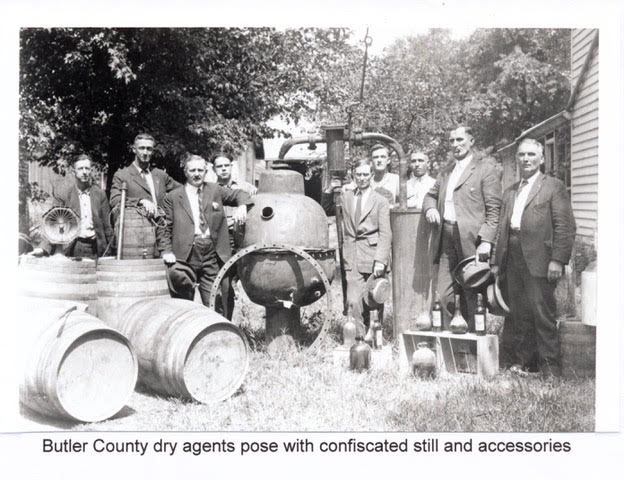

But the quiet start belied the prohibition-related problems and violence which soon would label Hamilton and vicinity as "Little Chicago," a haven for bootleggers.

Lyman Williams

When Prohibition first kicked in, Lyman Williams led a consortium of saloon owners to purchase a special license to remain open one last day, and earned the admiration of the city by throwing one last legal party.

Although Williams told the newspapers that he would likely just start serving soft drinks instead of hard ones, he remained one of the most active bootleggers and moonshiners in Hamilton, but he managed to mostly stay out of the limelight during the Little Chicago gangster wars. Toward the end of his career, as he was about to be hauled off to federal prison in Atlanta, the Cincinnati papers crowned him “King of the Hamilton bootleggers.”

In addition to operating the last legal saloon, Williams was one of the first Hamilton cafe owners to be fined for violating the Volstead act when on October 10, 1919, not quite five months into the dry era, he paid a fine of $1,000, equivalent to more than $14,000 in 2019 dollars, for selling beer stronger than 2.75 percent alcohol.

For years, according to local authorities, Lyman Williams has been recognized as a leader among Hamilton’s bootleggers, defying raiders with an establishment almost in the center of the business district. Several times he slipped from under because his employees or friends took the rap.Williams’s two and a half year sentence was the heaviest meted out to a Butler County bootlegger.

Although Williams told the newspapers that he would likely just start serving soft drinks instead of hard ones, he remained one of the most active bootleggers and moonshiners in Hamilton, but he managed to mostly stay out of the limelight during the Little Chicago gangster wars. Toward the end of his career, as he was about to be hauled off to federal prison in Atlanta, the Cincinnati papers crowned him “King of the Hamilton bootleggers.”

In addition to operating the last legal saloon, Williams was one of the first Hamilton cafe owners to be fined for violating the Volstead act when on October 10, 1919, not quite five months into the dry era, he paid a fine of $1,000, equivalent to more than $14,000 in 2019 dollars, for selling beer stronger than 2.75 percent alcohol.

For years, according to local authorities, Lyman Williams has been recognized as a leader among Hamilton’s bootleggers, defying raiders with an establishment almost in the center of the business district. Several times he slipped from under because his employees or friends took the rap.Williams’s two and a half year sentence was the heaviest meted out to a Butler County bootlegger.