1913 Flood

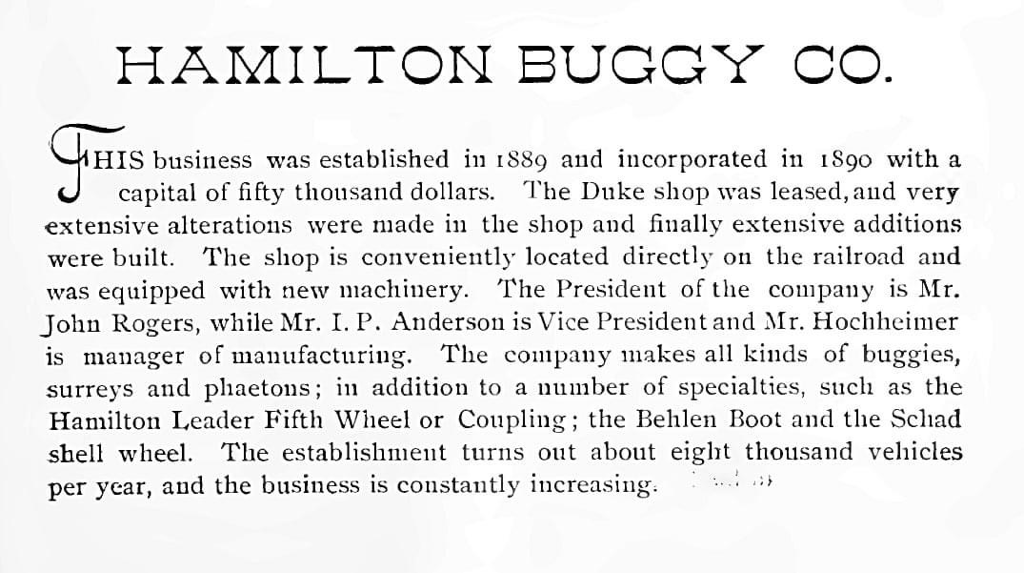

Script

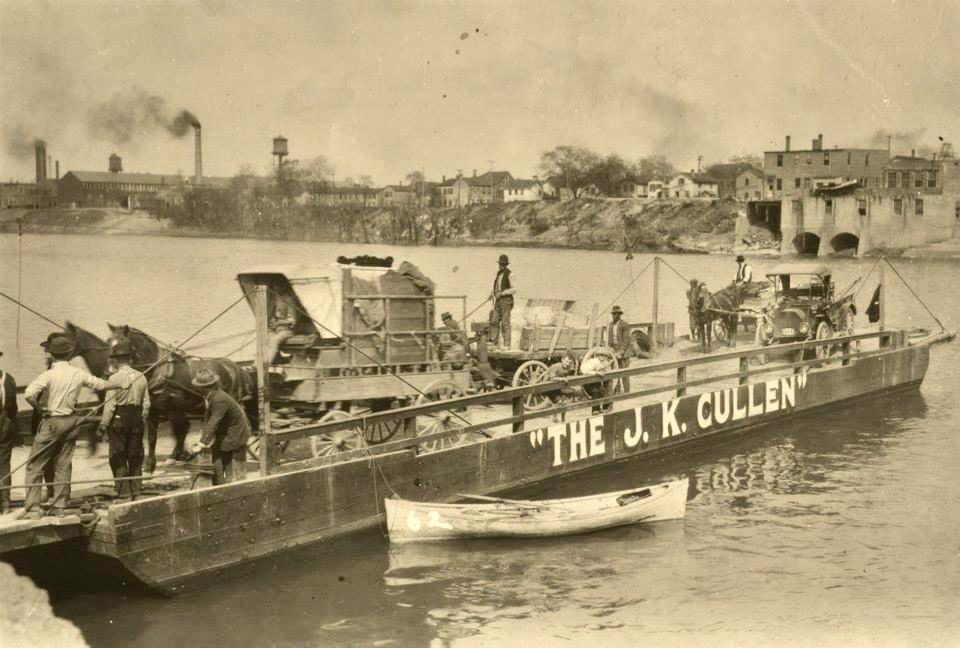

The WestSide was isolated after the flood. The bridges were gone. The 24” water main also washed away.

For 5 weeks Champion Paper, where Spooky Nook is now located, supplied electricity and water to the west side of the city.

For 5 weeks Champion Paper, where Spooky Nook is now located, supplied electricity and water to the west side of the city.

285 people died as a result of the flood. 10,000 people were homeless for months after the flood.

Below: The Holcomb & Hyde Building at high tide

1913 Flood

Geographic and geological evidence shows that floods have occurred throughout the valley since prehistoric times. Since European-American settlement, diaries, anecdotes, folk tales, letters, and official records have provided documentation of relatively common severe floods in 1814, 1828, 1832, 1847, 1866, 1883, 1897, 1898, and 1907.

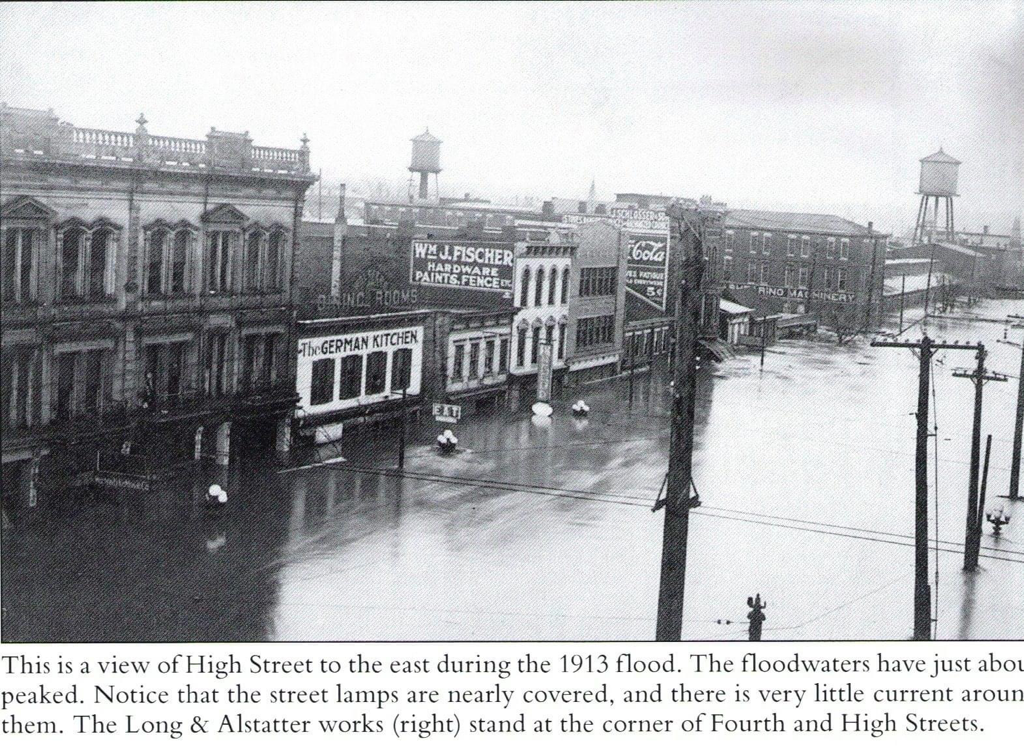

The Great Flood in Hamilton, Ohio at left is North 3d Street

Wrecked pontoon Bridge Hamilton Ohio

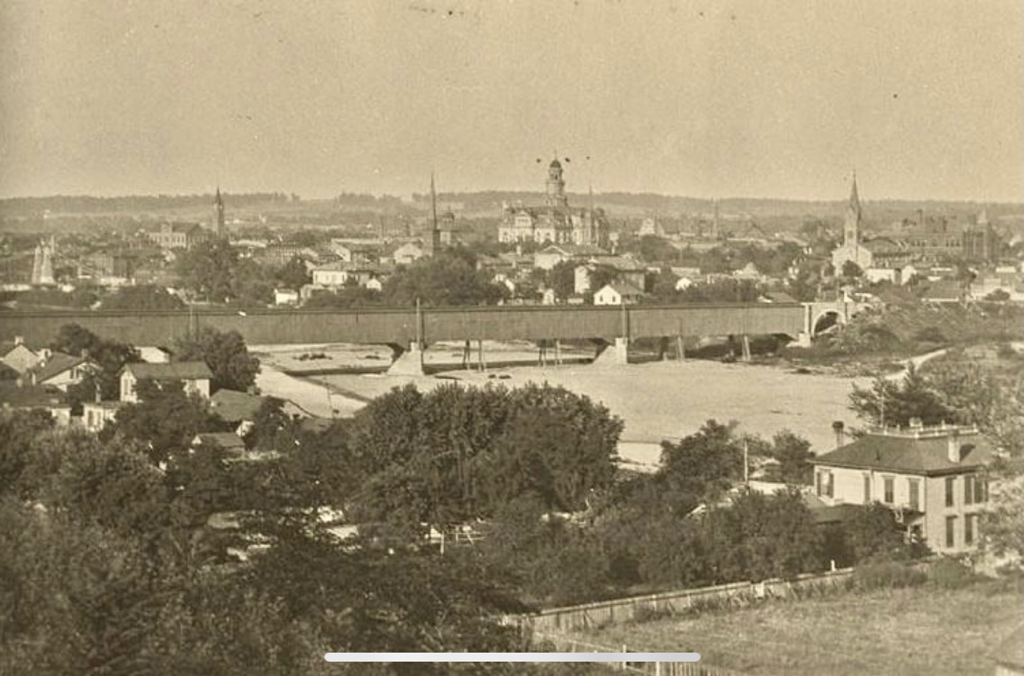

In March 1913 the greatest flood occurred. Heavy rain fell over the entire watershed, and the ground was frozen, as well as saturated from previous lighter rains. This resulted in a high rate of run-off from the rain: an estimated 90% flowed directly into the streams, creeks, and rivers. Between 9 and 11 inches of rain fell over five days, March 25 to March 29, 1913. An amount equivalent to about 30 days' discharge of water over Niagara Falls flowed through the Miami Valley during the ensuing flood. In the Great Miami River Valley, 360 persons died, about 200 of whom were from Hamilton. Some drowned, some were washed away and never found, others died from various diseases and complications, and some committed suicidebecause of severe losses. Damage in the valley was calculated at $100 million, the equivalent of $2 billion in 21st-century value. The flood waters were so powerful that within two hours they destroyed all four of Hamilton's bridges: Black Street, High-Main Street, Columbia, and the railroad bridge.

In Hamilton the flood waters rose with unexpected and frightening suddenness, reaching over three to eight feet in depth in downtown, and up to eighteen feet in the North End, along Fifth Street and through South Hamilton Crossing. The waters spread from D Street on the west to what is now Erie Highway on the east. The waters' rise was so swift that many people were trapped in the upper floors of businesses and houses. In some cases, people had to escape to their attics, and then break through the roof as the waters rose even higher. Temperatures hovered near freezing. The water current varied, but in constricted locations it raced at more than twenty miles per hour. The dead people, more than 1,000 drowned horses, other livestock, and pets, and sewage tainted the water. Nearly one-third of the population was left homeless and displaced: 10,000 of the 35,000 residents of Hamilton. Thousands of houses were destroyed by the flood; afterward, many that were too damaged to repair had to be demolished by city workers.

Miami Conservancy DistrictEditFollowing the disastrous 1913 flood in the Great Miami River Valley, residents realized that the only way to prevent future flooding was to deal with protection on a watershedbasis. Citizens from all the major cities in the valley, Piqua, Troy, Dayton, Carlisle, Franklin, Miamisburg, Middletown, and Hamilton, gathered together to find a solution and worked with legislative representatives to draft enabling legislation to create the Miami Conservancy District. It was passed by the state and signed into law by Governor James Cox. Although challenged several times in the courts, the laws withstood those attacks. The law and District have also withstood the tests of time. By 1915, the District hired an engineering staff, which developed plans for valley-long channel improvements, levees, and storage basins to temporarily retain excessive rains. The system was designed to withstand rains and flows that would be up to 40% greater than those of 1913. Waters have been retained more than 1,000 times, thereby preventing flooding. Construction began in 1915 and was completed in 1923. The Miami Conservancy District was the first of its kind in the nation, and has been an example of flood control protection. It is unique for having been developed, built, and supported financially just by those who benefit. The Miami Conservancy District is financially supported by an assessment on each property that was affected by the 1913 waters, related to the present value of the property because it is not at risk of flooding. All the other areas within the District are assessed because they benefit by reducing or eliminating danger to infrastructure, commerce, and transportation.

Geographic and geological evidence shows that floods have occurred throughout the valley since prehistoric times. Since European-American settlement, diaries, anecdotes, folk tales, letters, and official records have provided documentation of relatively common severe floods in 1814, 1828, 1832, 1847, 1866, 1883, 1897, 1898, and 1907.

The Great Flood in Hamilton, Ohio at left is North 3d Street

Wrecked pontoon Bridge Hamilton Ohio

In March 1913 the greatest flood occurred. Heavy rain fell over the entire watershed, and the ground was frozen, as well as saturated from previous lighter rains. This resulted in a high rate of run-off from the rain: an estimated 90% flowed directly into the streams, creeks, and rivers. Between 9 and 11 inches of rain fell over five days, March 25 to March 29, 1913. An amount equivalent to about 30 days' discharge of water over Niagara Falls flowed through the Miami Valley during the ensuing flood. In the Great Miami River Valley, 360 persons died, about 200 of whom were from Hamilton. Some drowned, some were washed away and never found, others died from various diseases and complications, and some committed suicidebecause of severe losses. Damage in the valley was calculated at $100 million, the equivalent of $2 billion in 21st-century value. The flood waters were so powerful that within two hours they destroyed all four of Hamilton's bridges: Black Street, High-Main Street, Columbia, and the railroad bridge.

In Hamilton the flood waters rose with unexpected and frightening suddenness, reaching over three to eight feet in depth in downtown, and up to eighteen feet in the North End, along Fifth Street and through South Hamilton Crossing. The waters spread from D Street on the west to what is now Erie Highway on the east. The waters' rise was so swift that many people were trapped in the upper floors of businesses and houses. In some cases, people had to escape to their attics, and then break through the roof as the waters rose even higher. Temperatures hovered near freezing. The water current varied, but in constricted locations it raced at more than twenty miles per hour. The dead people, more than 1,000 drowned horses, other livestock, and pets, and sewage tainted the water. Nearly one-third of the population was left homeless and displaced: 10,000 of the 35,000 residents of Hamilton. Thousands of houses were destroyed by the flood; afterward, many that were too damaged to repair had to be demolished by city workers.

Miami Conservancy DistrictEditFollowing the disastrous 1913 flood in the Great Miami River Valley, residents realized that the only way to prevent future flooding was to deal with protection on a watershedbasis. Citizens from all the major cities in the valley, Piqua, Troy, Dayton, Carlisle, Franklin, Miamisburg, Middletown, and Hamilton, gathered together to find a solution and worked with legislative representatives to draft enabling legislation to create the Miami Conservancy District. It was passed by the state and signed into law by Governor James Cox. Although challenged several times in the courts, the laws withstood those attacks. The law and District have also withstood the tests of time. By 1915, the District hired an engineering staff, which developed plans for valley-long channel improvements, levees, and storage basins to temporarily retain excessive rains. The system was designed to withstand rains and flows that would be up to 40% greater than those of 1913. Waters have been retained more than 1,000 times, thereby preventing flooding. Construction began in 1915 and was completed in 1923. The Miami Conservancy District was the first of its kind in the nation, and has been an example of flood control protection. It is unique for having been developed, built, and supported financially just by those who benefit. The Miami Conservancy District is financially supported by an assessment on each property that was affected by the 1913 waters, related to the present value of the property because it is not at risk of flooding. All the other areas within the District are assessed because they benefit by reducing or eliminating danger to infrastructure, commerce, and transportation.

Bread line at the High school after the 1913 flood

Above: The steel sided railroad collapsed into the river. This created a large dam flooding Hamilton even more than it already was.