Pierre Joseph Celeron

Forty-two years before the United States Army started building Fort Hamilton, France believed it owned this region. To reassert its claim to the area, the governor of New France authorized a combined diplomatic and military expedition under the direction of Pierre Joseph Celoron, sieur de Blainville.

The 56-year-old captain -- previously in command of French outposts at Niagara, Detroit and Mackinac -- was ordered to emphasize France's ownership of the land north of the Ohio River. His expedition also was meant to warn traders from British colonies to leave the region, and to persuade the Native Americans residing there that they should trade exclusively with the French.

For most of the 140 years after England had founded Jamestown in 1607 and France had established its first settlement at Quebec in 1608, the North American domains of the European rivals had been separated by the rugged Appalachian range.

During that period, the French developed a lucrative government-controlled fur trade with the Indians west of the mountains while the British built colonies -- including farming and industry -- on the east coast.

Those contrasting economic policies influenced population trends. By 1750, British colonists in North America outnumbered their French counterparts by a 20-1 ratio (about 1.6 million to 80,000).

In the 1740s, however, English colonists had started to replace the French in dealing with the Native Americans. Virginians and Pennsylvanians were offering the Indians a better deal for pelts. Fur trapped and prepared by the Miami, Shawnee and other Ohio-Indiana tribes found its way to Philadelphia and New York instead of Montreal.

More recently, the British government had authorized settlement in the region. The Ohio Company -- chartered May 19, 1749, by King George II of England -- was granted 500,000 acres on the upper Ohio.

To thwart the move of British colonists into the Ohio Valley, the French governor, Comte de Galissonniere, ordered Blainville's 1749 mission into the region. It would take about five months and cover, by various estimates, from 2,000 to 3,000 difficult miles.

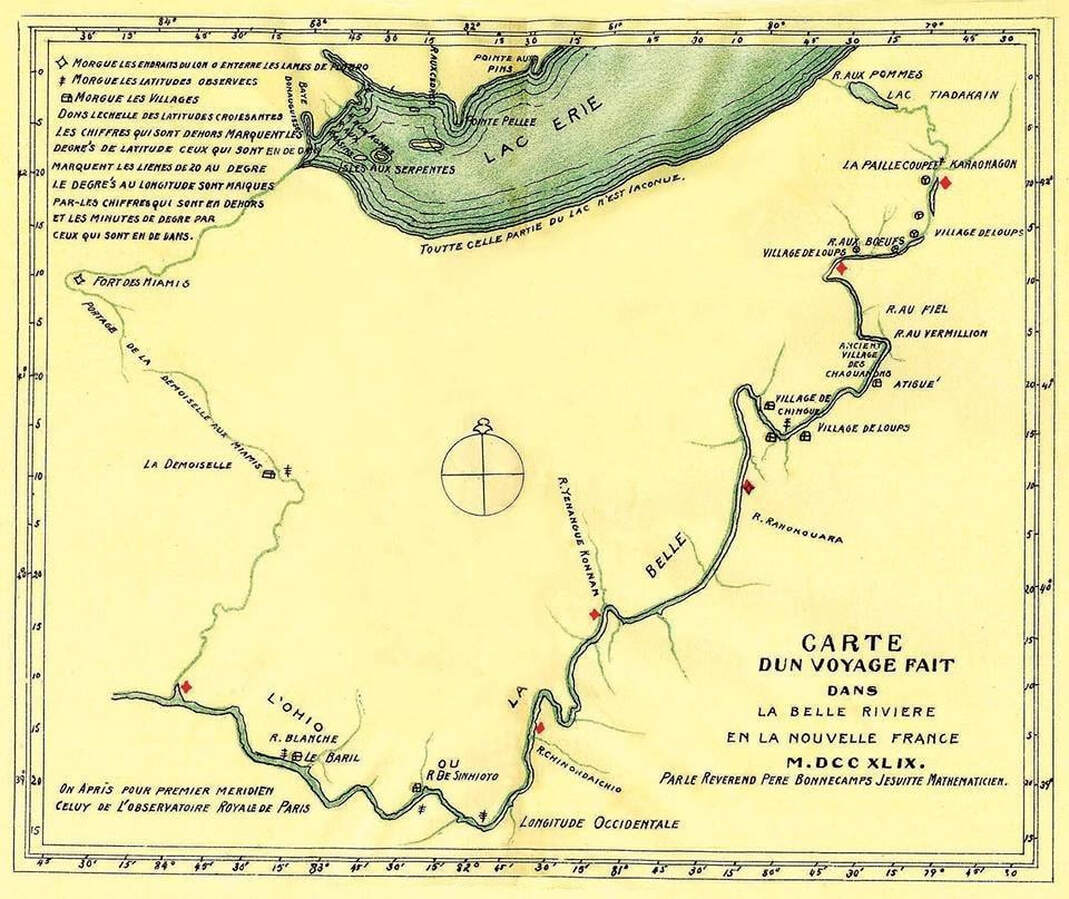

Blainville left Montreal June 15 with about 250 men, including 20 French regulars, 180 Canadian militia and about 30 Indians. In the group was a priest, Father Joseph Pierre de Bonnecamps, whose journal supplemented the commander's reports.

The French force headed southwest from Montreal along the St. Lawrence River to Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. From the latter, Blainville moved by smaller streams and portage to the upper part of the Allegheny River, which, with the Monongahela River, forms the Ohio River at present Pittsburgh.

By Mid-August 1749, he had reached the eastern border of what would become the state of Ohio.

To reassert the authority of King Louis XV over the region, Blainville's men placed 7x11-inch lead plates at the mouths of Wheeling Creek and the Muskingum, Great Kanawha and Great Miami rivers.

The six inscribed plates also were to remind the British colonists that they didn't belong in the area - a hollow warning because they were lettered in French. Many of the English-speaking fur traders venturing west of the Appalachians, who were unable to read and write their own language, couldn't decipher French.

During the journey, Blainville witnessed examples of the presence of his rivals. In an Indian village at Logstown (about 18 miles below present Pittsburgh) he saw six English colonist with 150 packs of fur. Later, he found five English-speaking traders at Shawneetown near the mouth of the Scioto River (present Portsmouth, Ohio).

He planted the last of his six plates Aug. 31, 1749, on the northeast bank of the confluence of the Ohio and Great Miami rivers, about 25 miles southwest of the site of Fort Hamilton, which would be constructed in 1791.

At the mouth of the Great Miami, he turned north for what would be, physically, the most difficult part of the campaign - and also his most disappointing encounter.

During the first two weeks of September 1749, a French force of about 250 men, following the Great Miami River, moved north through the future site of Hamilton toward an important rendezvous with a Miami leader.

Celoron de Blainville's expedition had started from Montreal June 15, 1749, on a multi-purpose mission along the Allegheny, Ohio and Great Miami rivers.

Blainville (also spelled Bienville) was charged with reasserting France's claim to the Ohio region, warning British colonists against trespassing and renewing friendship and trade with Native Americans in the area.

With great ceremony, he left behind six lead plates. The last was placed at the mouth of the Great Miami River - which the French called the Rock River - Aug. 31.

That plate said:

"The year 1749, we, Celoron, Knight of the Royal and Military Order of St. Louis, Captain, commanding a detachment sent by the orders of M. the Marquis de la Galossoniere, governor-general of Canada, upon the Beautiful River, otherwise called the Ohio, accompanied by principal officers of our detachment, have buried at the point formed by the right bank of the Ohio and the left bank of Rock River, a leaden plate, and have attached to a tree the arms of the king. In testimony whereof, we have drawn up and signed with Messrs. the officers, the present official statement."

Most of the trip had been downstream, but the move from the juncture of the Ohio and Great Miami rivers was upstream, a feat complicated by the condition of the river.

"Owing to the scarcity of water in this river," Blainville wrote, "it took 13 days in ascending it." Because of the low level of the Great Miami, about half of his force had to travel over land to a major stop at Pickawillany (north of present Piqua), then the center of the Miami fur industry.

In preceding years, the French had lost their monopoly in the fur trade with Native Americans in the region to British colonists from Virginia and Pennsylvania.

Instrumental in that business reversal was a Miami chief, Old Britain (also known as Old Briton, LaDemoiselle and Memeskia), who had earned that name switching his allegiance to British interests.

Blainville was there to convince Old Britain that he should revert to his old ways and grant the French exclusive access to fur coming from the Ohio-Indiana region.

But the Miami leader wasn't receptive and by Sept. 20, Blainville began a portage to the north-flowing Maumee River. The expedition -- traveling via Fort Detroit -- returned to Montreal Nov. 9, 1749.

In his report on the five-month campaign, according to one translation, Blainville said "all I can say is that the (Indian) nations of these places are very ill disposed against the French and entirely devoted to the English."

In January 1750, Old Britain punctuated his rejection of the French when he had three captured French soldiers executed and cut off the ears of a fourth man before sending him back to the governor of New France.

In June 1752 about 200 French and Indians returned to Pickawillany, where they destroyed the village on the Great Miami River. Fourteen Miami and one trader were killed in the assault, including Old Britain, who was boiled and eaten.

Historians disagree on the starting event and dates of the French and Indian War. Some consider the 1752 Pickawillany raid the first blow in an epochal struggle between France and Great Britain in North America.

The French and Indian War -- part of the global Seven Years' War -- ended Feb. 10, 1763, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris by Great Britain, France and Spain.

In that document, Spain gave up Florida to England, and France ceded New France (Canada) and its territory east of the Mississippi River to the British, retaining only two islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Within a dozen years of the treaty, the British would face a new challenge in North America. This time its authority would be contested by rebellious English-speaking colonists, not a foreign power.