The Rossville Hydraulic

An article written by Alta Harvey Heiser from the Hamilton Journal-News, November 7, 1936. The digitizing is very hard to read, so I transcribed the article as best I could.

Early Hydraulic History Shows Continuous Breaks

By Alta Harvey Heiser, Hamilton Journal-The Daily News, Hamilton, Ohio, November 7, 1936.

The people of Rossville yielded to Engineer Forrer’s (Samuel Forrer) decision that the hydraulic should be on the east side of the Great Miami river, because the grade was better there and the bed of Old river provided an excellent location for the grand reservoir, but they were by no means content and wanted a hydraulic of their very own. We have evidence of this in an 1845 letter written by William Bebb, then governor of Ohio, to John Woods, recently commissioned auditor of state. Both men were deeply concerned in and involved by the new hydraulic, and the governor asked Mr. Woods to meet him and his brother to see about “matters in general and the hydraulic in particular.” Evan R. Bebb had just bought up $4,000 worth of hydraulic stock.

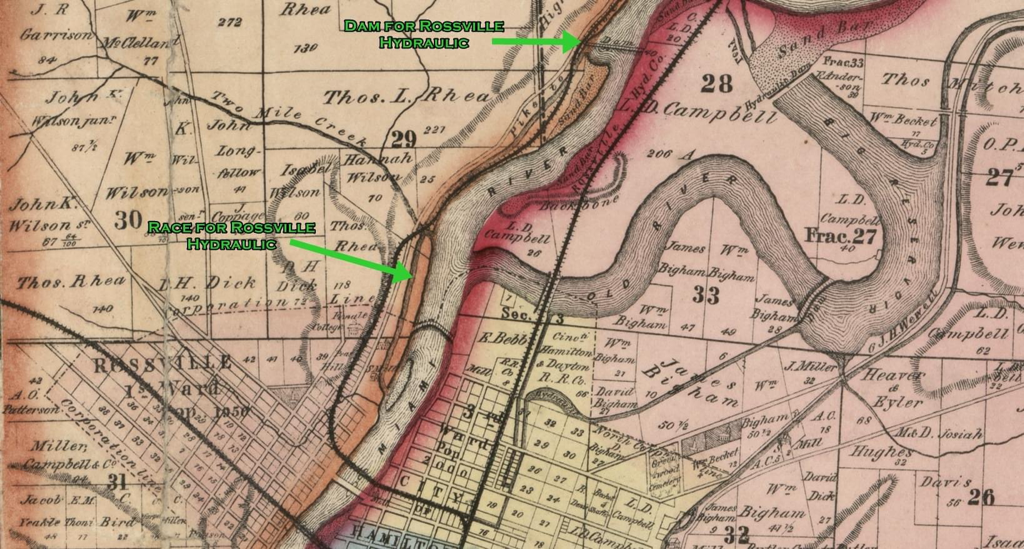

In this letter, Governor Bebb said: “Our Rossville people are making a great blow about their hydraulic and we must consider that matter.” Rossville got its hydraulic. The company was incorporated in February of 1845 by Robert B. Millikin, James Rossman, John K. Wilson, Robert Beckett, Samuel Snively, Henry Traber, Charles K. Smith, William Daniels, Alfred Thomas, Wilkeson Beatty, and Joshua Delaplane. Henry Clayton was the first engineer and was succeeded by Henry Earhart who fixed the location. Water was taken from the river just below the mouth of Fourmile creek and tunneled under Twomile. Connor McGreevy and John Connaughton were the contractors and started excavating in 1849. Some time later the dam was injured in a flood, and was made 200 feet longer and repaired “in a permanent manner.”

There was no PWA in those days and it seems incredible that the people started such big projects when money was almost a minus quantity. The directors evidently tried to bring prosperity by these public improvements, but they had a difficult task.

The tradespeople felt that Bebb and Woods would make good, and honored their orders. In this way, when there was no money with which to pay the workmen, they were given orders on certain merchants and thus secured food and clothing. The promoters of the public works were everlastingly optimistic. They seemed not to hesitate in incurring great debts, and usually there was a way out.

After the hydraulic had been in use a few months, Mr. Bebb wrote to Mr. Woods: “Ross and Lemmon (sic) want us to build another factory for them this fall -- what shall be done? I think the stock would be taken at once – the high price of pork will make money plenty and even farmers liberal.”

We cannot say just what the farmers were getting for their produce in 1845, but Andrew McCleary, at his place of business in Rossville sold lard for six cents a pound and “round stakes (sic)” at three cents a pound. The governor’s prediction of “plenty money” was in error. In June of 1846 Andrew McCleary wrote to Mr. Woods that he had been unable to raise funds for the hydraulic and “respecting the draft, it will not be convenient to meet it before the first of July. You will please hold your horses till that time.”

With Bebb and Woods both in office at Columbus, Lewis D. Campbell was in control of hydraulic affairs. There were those in Hamilton who felt that things were not managed right, and repeatedly wrote to Mr. Woods on the subject. He even was urged to resign as auditor of state and “save Hamilton” by heading hydraulic affairs again.

Campbell himself wrote concerning his handicaps: “I have been anxiously looking for a letter from you, hoping to hear you had made some arrangements for hydraulic funds. The truth is I cannot get along. I suffer for the $1,000 I lent in May and must by some means raise it. ---- I send a blank note. If you can make no arrangements to relieve me, sign it and send it by return mail. I will get the other signatures and go to Cincinnati and make one desperate effort.”

The blank note was not used, but whatever money was raised was soon exhausted.

Hydraulic Breaks

The story of the early days of the hydraulic is a story of continuous breaks. The directors retired at night almost with the expectation of being wakened before morning by the call” “Hello, The house, The hydraulic broke.” This meant a hurried scrambling into old clothes and rubber boots and snatching a lantern and shovel, instead of the customary more leisurely donning of broadcloth and top hat and selecting a gold-headed cane before starting out. There was work to be done and these men helped.

Governor Bebb returned to Hamilton in the fall of 1846 to find a break in the hydraulic and his daughter Mary very sick and under the care of young Dr. Falconer. He went to the place of the break, directing the work, and having the men clean out logs and the tail races at the same time. On the seventeenth of November he wrote that he had not been able to write a word of his inaugural address. He urged Mr. Woods to try to get down, as hydraulic affairs needed attention. A week later he wrote that Mary was better, her mother quite sick, and business pressing. The water was in the hydraulic again and all the factories running. George Graham had bought out Mr. Ross and was starting a great foundry. The inaugural address was finally written, but this had been under great difficulties.

A few months later Mr. Campbell wrote to Mr. Woods: “Your suggestion that all weak places should be made permanent is good. I fear, however, that you overlook one important consideration. How are we to pay? The Dutch and Irish beset me even when prostrate on my back and I do swear that is is insufferable.” To this Mr. Woods replied that he had made a pretty good sale and would try his hand at raising a little more cash in Columbus. If he succeeded, he would come to Hamilton with his pockets full of money!

It was indeed hard for these men to attend to “affairs of state” while the home town projects needed their attention.

Next week we shall learn how Mr. Campbell saved the hydraulic with his “anti-engineer” floodgate.

Early Hydraulic History Shows Continuous Breaks

By Alta Harvey Heiser, Hamilton Journal-The Daily News, Hamilton, Ohio, November 7, 1936.

The people of Rossville yielded to Engineer Forrer’s (Samuel Forrer) decision that the hydraulic should be on the east side of the Great Miami river, because the grade was better there and the bed of Old river provided an excellent location for the grand reservoir, but they were by no means content and wanted a hydraulic of their very own. We have evidence of this in an 1845 letter written by William Bebb, then governor of Ohio, to John Woods, recently commissioned auditor of state. Both men were deeply concerned in and involved by the new hydraulic, and the governor asked Mr. Woods to meet him and his brother to see about “matters in general and the hydraulic in particular.” Evan R. Bebb had just bought up $4,000 worth of hydraulic stock.

In this letter, Governor Bebb said: “Our Rossville people are making a great blow about their hydraulic and we must consider that matter.” Rossville got its hydraulic. The company was incorporated in February of 1845 by Robert B. Millikin, James Rossman, John K. Wilson, Robert Beckett, Samuel Snively, Henry Traber, Charles K. Smith, William Daniels, Alfred Thomas, Wilkeson Beatty, and Joshua Delaplane. Henry Clayton was the first engineer and was succeeded by Henry Earhart who fixed the location. Water was taken from the river just below the mouth of Fourmile creek and tunneled under Twomile. Connor McGreevy and John Connaughton were the contractors and started excavating in 1849. Some time later the dam was injured in a flood, and was made 200 feet longer and repaired “in a permanent manner.”

There was no PWA in those days and it seems incredible that the people started such big projects when money was almost a minus quantity. The directors evidently tried to bring prosperity by these public improvements, but they had a difficult task.

The tradespeople felt that Bebb and Woods would make good, and honored their orders. In this way, when there was no money with which to pay the workmen, they were given orders on certain merchants and thus secured food and clothing. The promoters of the public works were everlastingly optimistic. They seemed not to hesitate in incurring great debts, and usually there was a way out.

After the hydraulic had been in use a few months, Mr. Bebb wrote to Mr. Woods: “Ross and Lemmon (sic) want us to build another factory for them this fall -- what shall be done? I think the stock would be taken at once – the high price of pork will make money plenty and even farmers liberal.”

We cannot say just what the farmers were getting for their produce in 1845, but Andrew McCleary, at his place of business in Rossville sold lard for six cents a pound and “round stakes (sic)” at three cents a pound. The governor’s prediction of “plenty money” was in error. In June of 1846 Andrew McCleary wrote to Mr. Woods that he had been unable to raise funds for the hydraulic and “respecting the draft, it will not be convenient to meet it before the first of July. You will please hold your horses till that time.”

With Bebb and Woods both in office at Columbus, Lewis D. Campbell was in control of hydraulic affairs. There were those in Hamilton who felt that things were not managed right, and repeatedly wrote to Mr. Woods on the subject. He even was urged to resign as auditor of state and “save Hamilton” by heading hydraulic affairs again.

Campbell himself wrote concerning his handicaps: “I have been anxiously looking for a letter from you, hoping to hear you had made some arrangements for hydraulic funds. The truth is I cannot get along. I suffer for the $1,000 I lent in May and must by some means raise it. ---- I send a blank note. If you can make no arrangements to relieve me, sign it and send it by return mail. I will get the other signatures and go to Cincinnati and make one desperate effort.”

The blank note was not used, but whatever money was raised was soon exhausted.

Hydraulic Breaks

The story of the early days of the hydraulic is a story of continuous breaks. The directors retired at night almost with the expectation of being wakened before morning by the call” “Hello, The house, The hydraulic broke.” This meant a hurried scrambling into old clothes and rubber boots and snatching a lantern and shovel, instead of the customary more leisurely donning of broadcloth and top hat and selecting a gold-headed cane before starting out. There was work to be done and these men helped.

Governor Bebb returned to Hamilton in the fall of 1846 to find a break in the hydraulic and his daughter Mary very sick and under the care of young Dr. Falconer. He went to the place of the break, directing the work, and having the men clean out logs and the tail races at the same time. On the seventeenth of November he wrote that he had not been able to write a word of his inaugural address. He urged Mr. Woods to try to get down, as hydraulic affairs needed attention. A week later he wrote that Mary was better, her mother quite sick, and business pressing. The water was in the hydraulic again and all the factories running. George Graham had bought out Mr. Ross and was starting a great foundry. The inaugural address was finally written, but this had been under great difficulties.

A few months later Mr. Campbell wrote to Mr. Woods: “Your suggestion that all weak places should be made permanent is good. I fear, however, that you overlook one important consideration. How are we to pay? The Dutch and Irish beset me even when prostrate on my back and I do swear that is is insufferable.” To this Mr. Woods replied that he had made a pretty good sale and would try his hand at raising a little more cash in Columbus. If he succeeded, he would come to Hamilton with his pockets full of money!

It was indeed hard for these men to attend to “affairs of state” while the home town projects needed their attention.

Next week we shall learn how Mr. Campbell saved the hydraulic with his “anti-engineer” floodgate.