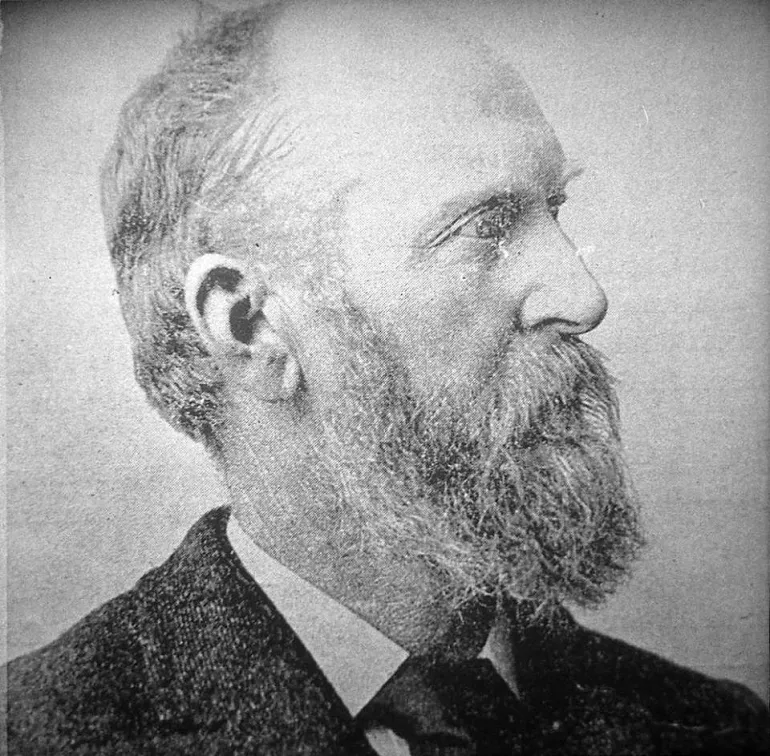

Peter Schwab

When he died, Peter Schwab was described as one of Butler County's "most picturesque citizens" by Gov. James M. Cox, himself a native of the county,

The German-born Schwab — who was reputed to be worth more than $400,000 when he died Sept. 13, 1913 — was regarded as Hamilton's most famous brewer during his nearly 40 years in that business.

Schwab — who pronounced his name "Swope" — showed both his audacity and business genius in naming his firm the Cincinnati Brewing Co.

By that move, he captured for his Hamilton brewery some of the prestige of the Queen City of the West, which in the last half of the 19th century was recognized as one of the world's finest brewing centers.

The Schwab brewery occupied a 200 by 400-foot tract at the northwest corner of the railroad, South Front Street and South Monument Avenue — now the site of Hamilton police headquarters and Hamilton Municipal Court.

Schwab's beer-making operations would pale in comparison with the 10,000-million gallon annual capacity of the soon-to-be opened Miller Brewery north of Hamilton.

But smallness didn't stop Schwab's Pure Gold beer from gaining a market which stretched from Washington, D. C., to St. Louis, and from Detroit and Pittsburgh into the southern states.

Schwab — who was born May 27, 1838, in Bavaria — came to the United States in 1850 at age 12. He landed at New Orleans, reached Cincinnati via the Mississippi and Ohio rivers and arrived in Hamilton on a canalboat.

His first job was as a cooper's apprentice. Sixteen years later, in 1866, he joined Henry Schlosser and James Fitton in a commission business in Cincinnati.

Two years later Schwab returned to Hamilton and with Ferdinand Van Derveer and Herman Reutti bought the brewery on South Front Street which had been started in 1858 by John W. Sohn.

Schwab left the partnership in 1870, but in 1874 he purchased the interests of both of his former colleagues.

After an 1875 incorporation, the brewery — with a capacity of only 50 barrels a day — became the Cincinnati Brewery Co. Within 15 years, Schwab's marketing skills had built it into a tough competitor in the middle third of the nation.

Meanwhile, Schwab also found time for several other businesses, real estate ventures, politics and public service in Hamilton and Butler County.

In the 1890s, he was the pioneer in promoting the building of the area's electric railways — more commonly known as interurbans or traction lines. He was a member of the board of trustees of the Cincinnati, Dayton and Toledo Traction Co. at his death.

Schwab, a Democrat, "was a power politically for years not only in Hamilton and throughout Butler County, but throughout the state and also in the nation," an newspaper obituary writer noted.

He also wielded that power for 12 years as a member of the Hamilton Board of Education, including eight years as its president. According to a newspaper tribute at his death, "much of the progress of the public schools of Hamilton was brought about under his administration."

Locally, he held only one other political position — as a member of the Hamilton sewer commission, when the city planned its sewer system and paved its first streets.

Schwab, a member of St. John Evangelical Protestant Church, also was a trustee of Mercy Hospital, which benefited from his charity, including daily donations of ice for the last 21 years of his life.

"Perhaps the one attribute in the life of Mr. Schwab of which little was known was his charity," said a Journal editorial in eulogizing the often-controversial brewer.

The writer noted that Schwab — who was regarded as an aggressive businessman — "chose . . that the world not know (of his charity) and that the secret of his acts of goodness and of help be known only to his Maker himself and the recipient."

The German-born Schwab — who was reputed to be worth more than $400,000 when he died Sept. 13, 1913 — was regarded as Hamilton's most famous brewer during his nearly 40 years in that business.

Schwab — who pronounced his name "Swope" — showed both his audacity and business genius in naming his firm the Cincinnati Brewing Co.

By that move, he captured for his Hamilton brewery some of the prestige of the Queen City of the West, which in the last half of the 19th century was recognized as one of the world's finest brewing centers.

The Schwab brewery occupied a 200 by 400-foot tract at the northwest corner of the railroad, South Front Street and South Monument Avenue — now the site of Hamilton police headquarters and Hamilton Municipal Court.

Schwab's beer-making operations would pale in comparison with the 10,000-million gallon annual capacity of the soon-to-be opened Miller Brewery north of Hamilton.

But smallness didn't stop Schwab's Pure Gold beer from gaining a market which stretched from Washington, D. C., to St. Louis, and from Detroit and Pittsburgh into the southern states.

Schwab — who was born May 27, 1838, in Bavaria — came to the United States in 1850 at age 12. He landed at New Orleans, reached Cincinnati via the Mississippi and Ohio rivers and arrived in Hamilton on a canalboat.

His first job was as a cooper's apprentice. Sixteen years later, in 1866, he joined Henry Schlosser and James Fitton in a commission business in Cincinnati.

Two years later Schwab returned to Hamilton and with Ferdinand Van Derveer and Herman Reutti bought the brewery on South Front Street which had been started in 1858 by John W. Sohn.

Schwab left the partnership in 1870, but in 1874 he purchased the interests of both of his former colleagues.

After an 1875 incorporation, the brewery — with a capacity of only 50 barrels a day — became the Cincinnati Brewery Co. Within 15 years, Schwab's marketing skills had built it into a tough competitor in the middle third of the nation.

Meanwhile, Schwab also found time for several other businesses, real estate ventures, politics and public service in Hamilton and Butler County.

In the 1890s, he was the pioneer in promoting the building of the area's electric railways — more commonly known as interurbans or traction lines. He was a member of the board of trustees of the Cincinnati, Dayton and Toledo Traction Co. at his death.

Schwab, a Democrat, "was a power politically for years not only in Hamilton and throughout Butler County, but throughout the state and also in the nation," an newspaper obituary writer noted.

He also wielded that power for 12 years as a member of the Hamilton Board of Education, including eight years as its president. According to a newspaper tribute at his death, "much of the progress of the public schools of Hamilton was brought about under his administration."

Locally, he held only one other political position — as a member of the Hamilton sewer commission, when the city planned its sewer system and paved its first streets.

Schwab, a member of St. John Evangelical Protestant Church, also was a trustee of Mercy Hospital, which benefited from his charity, including daily donations of ice for the last 21 years of his life.

"Perhaps the one attribute in the life of Mr. Schwab of which little was known was his charity," said a Journal editorial in eulogizing the often-controversial brewer.

The writer noted that Schwab — who was regarded as an aggressive businessman — "chose . . that the world not know (of his charity) and that the secret of his acts of goodness and of help be known only to his Maker himself and the recipient."

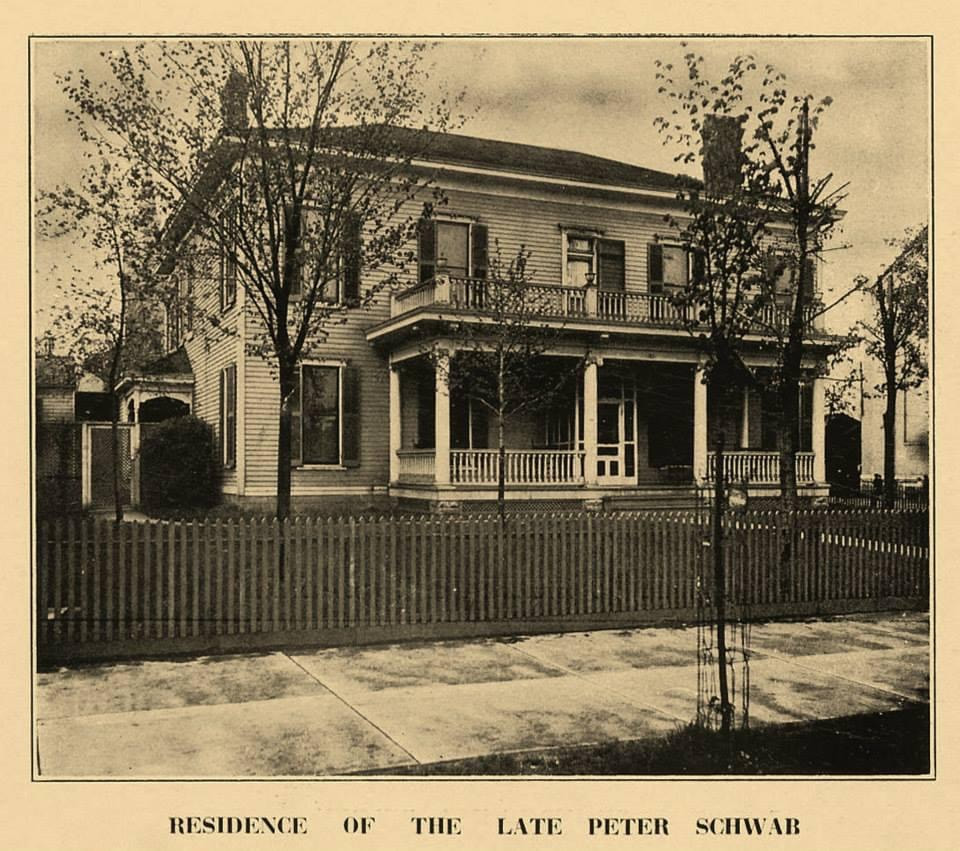

From JustHamilton.com : “And Peter Schwab is dead.”So reads the lead story of the Hamilton Evening Journal on September 15, 1913, one simple sentence that expressed the profound sorrow that had spread across the city on the passing of “Uncle Peter,” as he was affectionately called by the press, and presumably, the people. Certainly, in his own advertising.

In addition to a lengthy obituary outlining his career and achievements, the editorial writers that day waxed eloquently about his passing: “The acquaintanceships, the friendships, the associations of Mr. Schwab extended far beyond the family circle, far beyond the circle of usual friendships and that is the reason that Hamilton mourns today as one family because one whom it knew so well, loved because of his generosity and respected because of his fearlessness, has passed from the activities of life into that mysterious realm shrouded in the mystery called death” [sic].

“One would not take him for a politician nor a brewer,” wrote a Cincinnati reporter. “Can you imagine a converted cowboy with an honest face, large feet, long legs, a sandy beard, a black sombrero and an enormous heart! … Peter is all wool and a yard wide.”

In many ways, the resume of Peter Schwab reads like “The Great American Dream Fulfilled.” Born 1838 in Bavaria, Schwab (who pronounced his name “Swope”) came to the Hamilton on a canal boat from New Orleans at the age of 12 and never lost his thick German accent. Here, he became a cooper’s apprentice, learning the craft of making barrels for brewing and distilling. He was, the obituary reads, “shrewd industrious and saving and in 1866 had accumulated sufficient of this world’s goods to embark upon a business career.”

In that year, it goes on, he became engaged in “the commission business,” and by 1874 was able to buy the Sohn Brewery at South Front and Sycamore streets, which eventually covered the entire block of the current police station. He renamed it “The Cincinnati Brewing Company,” and marketed a regionally-popular lager under the brand name “Pure Gold” as “the beer that made Milwaukee jealous” and “the King of Bottled Beers.” He added an ice-making facility in later years, the only part of the enterprise that survived Prohibition.

Schwab is also credited for bringing the electric street cars, known as “traction lines”, to Hamilton and Butler County, taking a personal hand in securing rights to the land. As a member of the Sewer Commission, he was instrumental in developing the city’s sewer system and in bringing paved roads to Hamilton. His philanthropy included a special interest in Mercy Hospital, supplying all the ice to the institution for free and keeping its laboratories outfitted with up-to-date equipment.

But above all, Peter Schwab was known as one of the most politically powerful men in Hamilton and Butler County, and consequently what was then the Third Congressional District where he had to contend with Montgomery County politicos. He was a staunch “old-line” Grover Cleveland democrat, and his only elected office, 12 years on the board of education, was but the iceberg tip of his influence. During his tenure as boss, the democratic party was so prominent in Hamilton that the power struggle was not between republicans and democrats so much as it was between the “Schwabite” faction of democrats and whatever faction was challenging him at the time.

But above all, Peter Schwab was known as one of the most politically powerful men in Hamilton and Butler County, and consequently what was then the Third Congressional District where he had to contend with Montgomery County politicos.

In a 1930 special section looking back on “the Gay Nineties,” the Hamilton Daily News wrote that the era was “the hey-day of Peter Schwab.”

It surmised, “Schwab, if all things told of him are true, was not an Easy Boss. He did things ruthlessly to those who opposed him. He had his enemies within and without his own party.”

Clearly, his power was not absolute, and sometimes his faction fell out of favor, as in the mid-1890s when two members of his school board and others in his party were participants in a dog fight at a Port Union ice house that ended in a brawl with a man shot dead. Chided in the next election as “the dog-fighting faction,” the Schwab clique’s power waned a bit and his struggle to maintain it found him accused of election chicanery for the second time in his career. Accusations against Schwab of ballot-stuffing date back to the 1870s, when Butler County Sheriff Robert W. Andrews saw Schwab open a ballot box and throw in a handful of tickets. The Sheriff testified that Schwab turned around and their eyes met. Startled, Schwab asked, “Did you see that?” The Sheriff, a democrat, replied, “I could not help seeing it, Peter.”

To understand the depth of his influence, it might be interesting to go back to space in the obituary between the apprenticeship and “the commission business” and unpack a little. It seems the local press had forgiven and forgotten a lot by the time of Uncle Peter’s death, because his rise to prominence includes a lot of accusations of thuggery and corruption, and more than one historical source gives Peter Schwab credit for single-handedly creating a whiskey ring that spanned the length of the Miami-Erie Canal in an elaborate scheme to beat the federal liquor tax.

In a June 7, 1870 the Cincinnati Enquirer published an article titled “OUR PETER. The King of the Whisky Ring_How Peter Schwab got Rich, as Related by a Correspondent of the New York Tribune,” which details Schwab’s “whisky and revenue frauds extending over two years and aggregating $3,000,000.” That translates to nearly $60 million in early twenty-first century dollars. This article corroborates many of the accusations later made against Schwab in the 1874 book credited to Thomas McGehean, although the latter is somewhat tainted by the politics of the day.

The article posits that prior to 1863, Schwab was “a poor and industrious mechanic, earning daily wages,” but his political enthusiasm earned him an appointment as constable of Fairfield Township, which included Hamilton. In the days before a professional police department, the constable was charged with maintaining peace and order, and was paid by presenting to the clerk of courts an invoice for every arrest made, whether the case went to trial or not. A normally diligent constable would have earned around five or six hundred dollars a year, McGehean says. During the 1862 term, however, the super-diligent young Schwab earned about $8,000. That seemed a bit excessive to those in charge, and there were allegations that some of the arrests were only on paper, so it became a law that for a constable to collect the fee, there must be a formal bill of indictment issued by a grand jury.

Nevertheless, with that money, Schwab funded a whiskey-buying operation and netted $200,000 by purchasing 100,000 barrels of whiskey just before the government clapped on a tax of $2 a gallon to fund the Civil War. With these proceeds, Schwab purchased an interest in one of Hamilton’s two distilleries. As he would later do with the breweries, he eventually bought out the other stakeholders. He turned his attention to other distilleries up and down the Miami-Erie Canal, purchasing at least a controlling interest in each so that he could install loyal men into critical positions that allowed him to skirt the federal whiskey taxes.

“He worked alone — in the dark,” the Enquirer reported. “It is doubtful if the very men he employed knew each other to be in his employ. There was no one to betray operations.”

A case was pending against him when this article appeared, continuing, “In the choice of his agents, the secrecy of his operations, the depth of his plans, the magnitude of his schemes, the audacity and prudence demanded and displayed, there are qualities developed sometimes wanting in the generals of armies. Of the many marvels of the Whisky Ring, his career has been the most marvelous. It will hardly be expected that the present investigation of his operations will amount to much. Well-paid agents are almost as poor as dead men at telling tales.” A New York Tribune article quipped that Schwab “rose to an understanding of the distilling business, and mastered its details better than the revenue officers.”

Although he was acquitted in the 1870 ballot stuffing case, the whiskey fraud eventually turned around to bite him and Schwab filed bankruptcy in 1872, his distilleries auctioned by the government to pay a judgement against him for unpaid taxes. Still, the next 20 years saw Schwab’s influence grow until it took the legislative power of the Ohio Senate to slow down the Schwab machine by enacting “the Hamilton Ripper Bill” in 1898, despite allegations that Schwab personally took suitcases full of cash to Columbus to stop it. The bill dismantled Hamilton’s city government and gave power to a five-man board, chosen by a judge that favored the faction led by the young upstart Charles E. Mason, but within two years, a new judge was elected and the power shifted enough to put the Schwabites back into power with Uncle Peter again at the helm, albeit behind the scenes and in the news.

However shady his origin story, Schwab remained a powerful businessman and influential politician throughout his life and earned a prominent place in Hamilton society and history. His pallbearers included three Rentchlers, two Fittons and a Schwenn — and a former Ohio Governor, James E. Campbell, a native of Hamilton whom Schwab converted from a Republican.

In addition to a lengthy obituary outlining his career and achievements, the editorial writers that day waxed eloquently about his passing: “The acquaintanceships, the friendships, the associations of Mr. Schwab extended far beyond the family circle, far beyond the circle of usual friendships and that is the reason that Hamilton mourns today as one family because one whom it knew so well, loved because of his generosity and respected because of his fearlessness, has passed from the activities of life into that mysterious realm shrouded in the mystery called death” [sic].

“One would not take him for a politician nor a brewer,” wrote a Cincinnati reporter. “Can you imagine a converted cowboy with an honest face, large feet, long legs, a sandy beard, a black sombrero and an enormous heart! … Peter is all wool and a yard wide.”

In many ways, the resume of Peter Schwab reads like “The Great American Dream Fulfilled.” Born 1838 in Bavaria, Schwab (who pronounced his name “Swope”) came to the Hamilton on a canal boat from New Orleans at the age of 12 and never lost his thick German accent. Here, he became a cooper’s apprentice, learning the craft of making barrels for brewing and distilling. He was, the obituary reads, “shrewd industrious and saving and in 1866 had accumulated sufficient of this world’s goods to embark upon a business career.”

In that year, it goes on, he became engaged in “the commission business,” and by 1874 was able to buy the Sohn Brewery at South Front and Sycamore streets, which eventually covered the entire block of the current police station. He renamed it “The Cincinnati Brewing Company,” and marketed a regionally-popular lager under the brand name “Pure Gold” as “the beer that made Milwaukee jealous” and “the King of Bottled Beers.” He added an ice-making facility in later years, the only part of the enterprise that survived Prohibition.

Schwab is also credited for bringing the electric street cars, known as “traction lines”, to Hamilton and Butler County, taking a personal hand in securing rights to the land. As a member of the Sewer Commission, he was instrumental in developing the city’s sewer system and in bringing paved roads to Hamilton. His philanthropy included a special interest in Mercy Hospital, supplying all the ice to the institution for free and keeping its laboratories outfitted with up-to-date equipment.

But above all, Peter Schwab was known as one of the most politically powerful men in Hamilton and Butler County, and consequently what was then the Third Congressional District where he had to contend with Montgomery County politicos. He was a staunch “old-line” Grover Cleveland democrat, and his only elected office, 12 years on the board of education, was but the iceberg tip of his influence. During his tenure as boss, the democratic party was so prominent in Hamilton that the power struggle was not between republicans and democrats so much as it was between the “Schwabite” faction of democrats and whatever faction was challenging him at the time.

But above all, Peter Schwab was known as one of the most politically powerful men in Hamilton and Butler County, and consequently what was then the Third Congressional District where he had to contend with Montgomery County politicos.

In a 1930 special section looking back on “the Gay Nineties,” the Hamilton Daily News wrote that the era was “the hey-day of Peter Schwab.”

It surmised, “Schwab, if all things told of him are true, was not an Easy Boss. He did things ruthlessly to those who opposed him. He had his enemies within and without his own party.”

Clearly, his power was not absolute, and sometimes his faction fell out of favor, as in the mid-1890s when two members of his school board and others in his party were participants in a dog fight at a Port Union ice house that ended in a brawl with a man shot dead. Chided in the next election as “the dog-fighting faction,” the Schwab clique’s power waned a bit and his struggle to maintain it found him accused of election chicanery for the second time in his career. Accusations against Schwab of ballot-stuffing date back to the 1870s, when Butler County Sheriff Robert W. Andrews saw Schwab open a ballot box and throw in a handful of tickets. The Sheriff testified that Schwab turned around and their eyes met. Startled, Schwab asked, “Did you see that?” The Sheriff, a democrat, replied, “I could not help seeing it, Peter.”

To understand the depth of his influence, it might be interesting to go back to space in the obituary between the apprenticeship and “the commission business” and unpack a little. It seems the local press had forgiven and forgotten a lot by the time of Uncle Peter’s death, because his rise to prominence includes a lot of accusations of thuggery and corruption, and more than one historical source gives Peter Schwab credit for single-handedly creating a whiskey ring that spanned the length of the Miami-Erie Canal in an elaborate scheme to beat the federal liquor tax.

In a June 7, 1870 the Cincinnati Enquirer published an article titled “OUR PETER. The King of the Whisky Ring_How Peter Schwab got Rich, as Related by a Correspondent of the New York Tribune,” which details Schwab’s “whisky and revenue frauds extending over two years and aggregating $3,000,000.” That translates to nearly $60 million in early twenty-first century dollars. This article corroborates many of the accusations later made against Schwab in the 1874 book credited to Thomas McGehean, although the latter is somewhat tainted by the politics of the day.

The article posits that prior to 1863, Schwab was “a poor and industrious mechanic, earning daily wages,” but his political enthusiasm earned him an appointment as constable of Fairfield Township, which included Hamilton. In the days before a professional police department, the constable was charged with maintaining peace and order, and was paid by presenting to the clerk of courts an invoice for every arrest made, whether the case went to trial or not. A normally diligent constable would have earned around five or six hundred dollars a year, McGehean says. During the 1862 term, however, the super-diligent young Schwab earned about $8,000. That seemed a bit excessive to those in charge, and there were allegations that some of the arrests were only on paper, so it became a law that for a constable to collect the fee, there must be a formal bill of indictment issued by a grand jury.

Nevertheless, with that money, Schwab funded a whiskey-buying operation and netted $200,000 by purchasing 100,000 barrels of whiskey just before the government clapped on a tax of $2 a gallon to fund the Civil War. With these proceeds, Schwab purchased an interest in one of Hamilton’s two distilleries. As he would later do with the breweries, he eventually bought out the other stakeholders. He turned his attention to other distilleries up and down the Miami-Erie Canal, purchasing at least a controlling interest in each so that he could install loyal men into critical positions that allowed him to skirt the federal whiskey taxes.

“He worked alone — in the dark,” the Enquirer reported. “It is doubtful if the very men he employed knew each other to be in his employ. There was no one to betray operations.”

A case was pending against him when this article appeared, continuing, “In the choice of his agents, the secrecy of his operations, the depth of his plans, the magnitude of his schemes, the audacity and prudence demanded and displayed, there are qualities developed sometimes wanting in the generals of armies. Of the many marvels of the Whisky Ring, his career has been the most marvelous. It will hardly be expected that the present investigation of his operations will amount to much. Well-paid agents are almost as poor as dead men at telling tales.” A New York Tribune article quipped that Schwab “rose to an understanding of the distilling business, and mastered its details better than the revenue officers.”

Although he was acquitted in the 1870 ballot stuffing case, the whiskey fraud eventually turned around to bite him and Schwab filed bankruptcy in 1872, his distilleries auctioned by the government to pay a judgement against him for unpaid taxes. Still, the next 20 years saw Schwab’s influence grow until it took the legislative power of the Ohio Senate to slow down the Schwab machine by enacting “the Hamilton Ripper Bill” in 1898, despite allegations that Schwab personally took suitcases full of cash to Columbus to stop it. The bill dismantled Hamilton’s city government and gave power to a five-man board, chosen by a judge that favored the faction led by the young upstart Charles E. Mason, but within two years, a new judge was elected and the power shifted enough to put the Schwabites back into power with Uncle Peter again at the helm, albeit behind the scenes and in the news.

However shady his origin story, Schwab remained a powerful businessman and influential politician throughout his life and earned a prominent place in Hamilton society and history. His pallbearers included three Rentchlers, two Fittons and a Schwenn — and a former Ohio Governor, James E. Campbell, a native of Hamilton whom Schwab converted from a Republican.