Robert McCloskey

| robert_mccloskey_tour_walkthrough_1_notes.docx |

| mccloskey_walking_tour.pdf |

His mother and father were deaf due to cholera. His father was killed when he got hit by a train. Not because he was deaf, because he ran to save a baby in a runaway carriage.

695. Aug. 8, 2001 -- Lentil will return to boyhood home in September:

Journal-News, Wednesday, Aug. 8, 2001

Lentil will return to boyhood home in September

By Jim Blount

There will be a homecoming next month for a Hamilton boy who left town more than 60 years ago. Miraculously, he hasn't aged since 1940. The lad -- who remains about 10 or 11 years old -- still has only one name, Lentil. The boy, his important harmonica and his dog are scheduled to reappear in the City of Sculpture Friday, Sept. 21.

Lentil is the creation of Robert McCloskey, a Hamilton native recognized by the Educational Paperback Association, a publishers' group, as among the top 50 authors for children in grades one to four. Lentil is the story of a boy in a typical Midwestern town, Alto, Ohio.

Through the sponsorship of the Hamilton Community Foundation, Nancy Schon is completing a sculpture of Lentil and his dog that will be unveiled Sept. 21 in the recently-created park at the northwest corner of High and North Front streets, formerly the site of the Rialto and Court theaters.

Lentil is one of three McCloskey works labeled his "Midwest boy books," reflecting his boyhood in Hamilton. The other titles are Homer Price and Centerburg Tales. They blend McCloskey's youthful interests in music, art and engineering with satire.

The key characters, Lentil and Homer Price, get into and out of a series of adventures and misadventures. The situations are preposterous, but engaging and entertaining stories.

Reviewers, critics and scholars have compared Lentil and Homer Price with Mark Twain's Tom Sawyer. McCloskey's work also has been likened to that of artist Norman Rockwell.

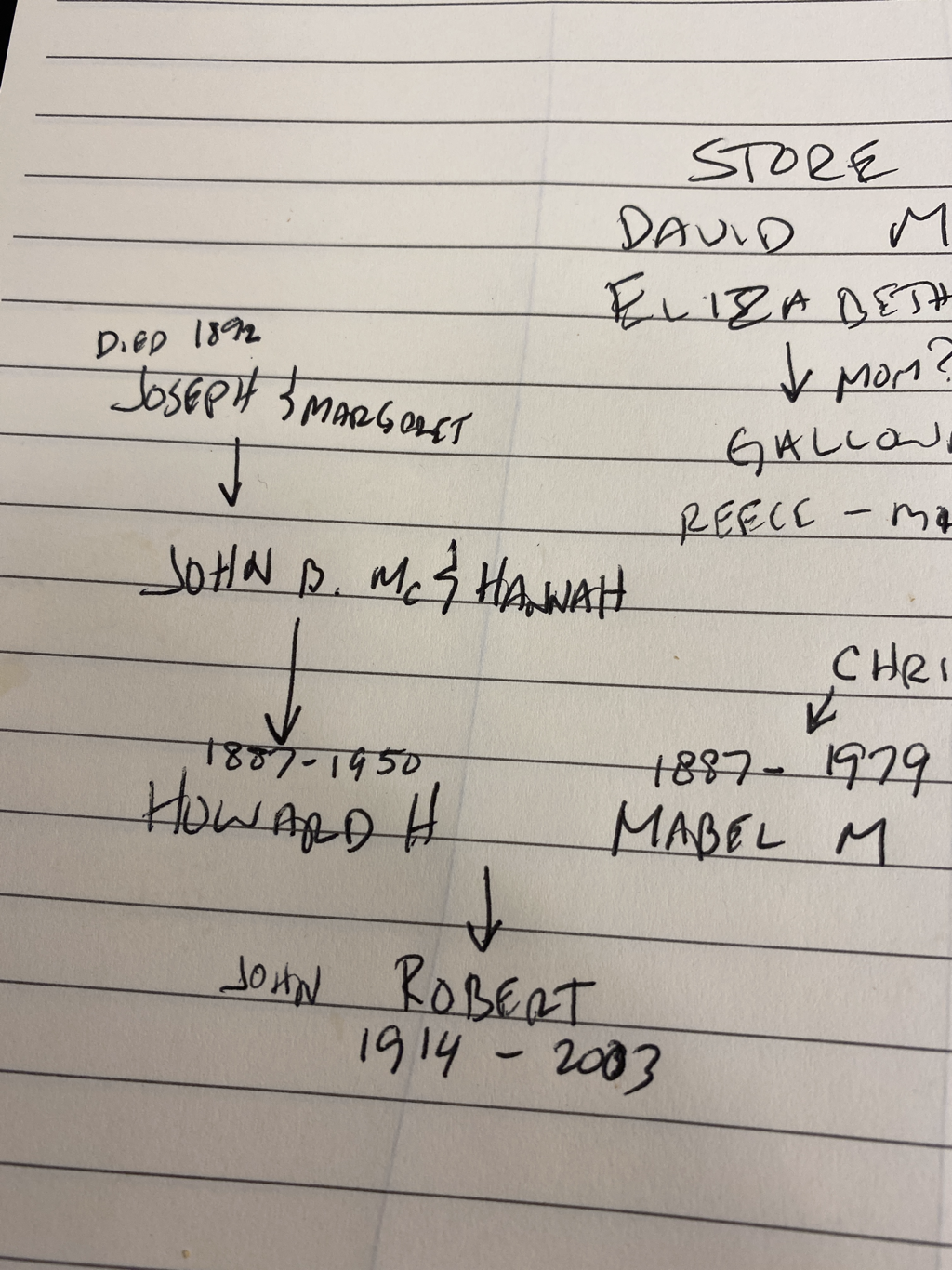

The award-winning author⁄ illustrator was born Sept. 15, 1914, in Hamilton, a son of Howard Hill McCloskey and Mabel Wismeyer McCloskey. His parents encouraged musical interests. "From the time my fingers were long enough to play the scale, I took piano lessons," McCloskey said later. "I started to play the harmonica, the drums, and then the oboe. The musician's life was the life for me -- that is, until I became interested in things electrical and mechanical."

Although named John Robert McCloskey, he never used the John. By high school, he had attained a nickname, Clutch.

After graduating from Hamilton High School in 1932, McCloskey studied at Boston's Vesper George Art School (1932-36) and New York's National Academy of Design (1936-38).

After some commercial work he disliked, McCloskey returned to Hamilton and began drawing and painting everyday things around him. The result was Lentil -- his first book.

McCloskey returned to New York, where Viking Press acquired the book. He submitted the draft in 1938, but it wasn't published until 1940. The New York Times called it "a book that, along with its fun, truly illustrates the American scene."

Lentil -- with fewer than 850 words -- is dominated by 30 illustrations. The suggested enjoyment level is ages 3 to 8.

Lentil couldn't sing or whistle, and couldn't pucker his lips. "When he opened his mouth to try, only strange sounds came out," McCloskey wrote, "so he saved up enough pennies to buy a harmonica."

Eventually, Lentil's harmonica skill saves the day in Alto -- and he becomes the community hero. In one illustration, Lentil is shown practicing the harmonica in a bathtub. McCloskey said "the bathtub, with its old wash basin, is the one upstairs in the house where I grew up" on Hamilton's West Side.

In another scene, the Alto band is led by a drum major -- a position that McCloskey held with the Hamilton High School band. Lentil is still leading the band in recent editions of Lentil, published -- along with other McCloskey books -- by Puffin Books and Viking Childrens Books, divisions of Penguin Putnam Inc.

There will be more about McCloskey and his books in another column.

# # #

696. Aug. 15, 2001 -- Homer Price also called Hamilton his boyhood home:

Journal-News, Wednesday, Aug. 15, 2001

Homer Price also called Hamilton his boyhood home

By Jim Blount

Lentil -- the 10 to 11 year-old-boy with only one name -- isn't the only character in Robert McCloskey's books who enjoyed a Hamilton boyhood. There also was Homer Price, the key person in two other volumes produced by the award-winning writer⁄illustrator born in Hamilton in 1914.

For now, Lentil will be a more familiar in the City of Sculpture. As of Sept. 21 -- thanks to the Hamilton Community Foundation -- a likeness of Lentil and his dog will be featured in the small downtown park at the northwest corner of High and North Front streets. The sculpture to be unveiled that day is the work of Nancy Schon, who has reproduced other McCloskey characters for parks in Boston and Moscow.

Unlike Lentil -- which was McCloskey's first book -- Homer Price and Centerburg Tales are more text than illustrations. Both are aimed at readers between the ages of 8 and 12, but they'll delight readers well beyond those ages who appreciate satire.

Homer Price -- the third book by the 1932 Hamilton High School -- was not planned. It was an accident, according to McCloskey. He said he wrote it when his publisher didn't have anything for him to illustrate.

In six stories in Homer Price, McCloskey looks back with humor and affection at his Hamilton childhood.

The book was well received by boys and girls across the United States when released in October 1943 -- during the middle of World War II. Gary D. Schmidt, a McCloskey biographer, said that "for some, Homer Price became a document stating what Americans were fighting for on the fields of Europe and the islands of the Pacific."

McCloskey was in the army when the book was published. He spent three years (1942-45) at Fort McClellan, Ala. As a technical sergeant, he produced illustrations for training materials.

The fictional Homer Price -- like the youthful McCloskey -- loves experimenting with gadgets, and there are plenty of them in the book.

None of the devices is more intriguing than a troublesome doughnut machine. It was suggested by one in the front window of the Elite, a bakery and coffee shop formerly at 212 High Street in downtown Hamilton.

And, what child wouldn't like a story about a skunk that helps catch the bad guys, or a tale of Homer and his friend, Freddy, not only meeting Super-Duper -- a poorly disguised spoof of Superman -- but coming to his rescue.

Centerburg Tales is a 191-page sequel to the 149-page Homer Price . A central figure is Grandpa Hercules, Homer's grandfather. "You can't tell whether he's 50 or 90, to look at him," said Freddy. "Grandpa Herc says that he stopped counting birthdays at 99."

In the 1951 book, "something always reminds Grandpa Herc of a story," and the kids of Centerburg are always willing to listen. Grandpa's fantastic stories are a mixture of history, fantasy and spoofs.

Biographer Gary D. Schmidt said McCloskey has been "identified as a writer and illustrator of American life, but perhaps it would be more accurate to say that he is a writer and illustrator of the child's life."

McCloskey "examines the child in the context of a family, drawing love and security from that family," said Schmidt, author of Robert McCloskey, published in 1990 by Twayne Publishers, Boston.

Books by the author and illustrator have sold more than 5.5 million copies around the world in many languages. Forty to 60 years after first publication, McCloskey's books continue to be recommended by educators, librarians and parents.

There will be more about McCloskey and his books in another column.

# # #

697. Aug. 22, 2001 -- Robert McCloskey: a duck's best friend:

Journal-News, Wednesday, Aug. 22, 2001

Robert McCloskey: a duck's best friend

By Jim Blount

Robert McCloskey has earned the title of "a duck's best friend." The Hamilton native's most popular book, Make Way for Ducklings , remains a child pleaser, although first published in 1938. The book has been translated into numerous foreign languages through about 60 editions. Scholastic calls it one of the 20 essential books for the very young.

The popular story -- McCloskey's second book -- evolved after he got a job in Boston, assisting Francis Scott Bradford in completing a mural of famous people of Beacon Hill.

"I had first noticed the ducks when walking through the Boston Public Garden every morning on my way to art school," he recalled. "When I returned to Boston four years later, I noticed the traffic problem of the ducks and heard a few stories about them. The book just sort of developed from there."

To draw perfectly proportioned ducks, he bought four mallards and kept them in his small apartment. "I spent the next weeks on my hands and knees, armed with a box of Kleenex and a sketchbook, following the ducks around the studio and observing them in the bathtub," he explained later.

The plot of the enduring book has been described this way: "Mr. and Mrs. Mallard find the perfect spot to raise their ducklings, at Boston's Public Garden. People feed them peanuts. It seems like a wonderful place to live until they are almost run over by a bicycle. Mrs. Mallard teaches her ducklings to swim, walk in a straight line and stay away from bicycles. But when they cross a busy street, thank goodness for Officer Michael. He stops traffic to make way for the ducklings."

The book's main characters -- Mrs. Mallard and her eight ducklings -- are perpetuated in bronze sculptures in Boston and Moscow.

Placed in Boston's Public Gardens in 1987, the work of Nancy Schon stretches along a 35-foot pathway of old Boston cobblestones. Mother duck stands 38 inches and her eight ducklings vary from 12 to 18 inches in height.

In 1991 -- in an act symbolic of the end of the 40-year Cold War -- First Lady Barbara Bush presented a replica to her Soviet counterpart, Raisa Gorbachev, who had admired the story and the Boston sculptures.

The plaque in a Moscow park reads: "This sculpture was given in love and friendship to the children of the Soviet Union on behalf of the children of the United States." Mrs. Gorbachev, who died in 1999, is buried in a cemetery near the park.

In September 2000, after the Moscow originals disappeared, Mrs. Mallard and three of her duckling were replaced in ceremonies including former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and the sculptor. (Nancy Schon has sculpted another McCloskey favorite -- Lentil -- which will be unveiled in Hamilton Sept. 21. It will feature the harmonica-playing boy and his dog.)

Make Way for Ducklings earned McCloskey the Caldecott Medal, given annually to the most distinguished American picture book for children. The medal is awarded by the Association of Library Services to Children, a division of the American Library Association.

How have McCloskey's words and illustrations maintained such stature? Biographer Gary D. Schmidt offered an explanation in his 1990 profile of the 1932 graduate of Hamilton High School.

"McCloskey's vision of children's literature is the more remarkable considering that the decades of his career in children's literature spanned the most turbulent time of the 20th century," Schmidt wrote. That range is from the end of the Depression and the start of World War II through the Korean War, the Cold War with its nuclear fears, assassinations and ending with the Vietnam War.

Schmidt said "in the midst of this dreadful world -- in the midst of folly and violence and threatened destruction -- appeared a series of books that celebrated childhood, family, friendship, the natural world -- in short, life itself." The biographer said McCloskey's books feature "warmth and security, family relationships, innocent joys, the freedom for children to grow and relish the unalloyed splendors and mysteries of the world that lies close about them."

Those traits have made the McCloskey books priceless and timeless -- stories that for 60-plus years have entertained children and pleased their parents.

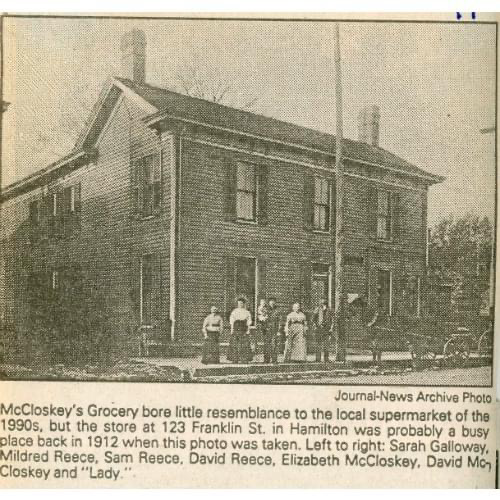

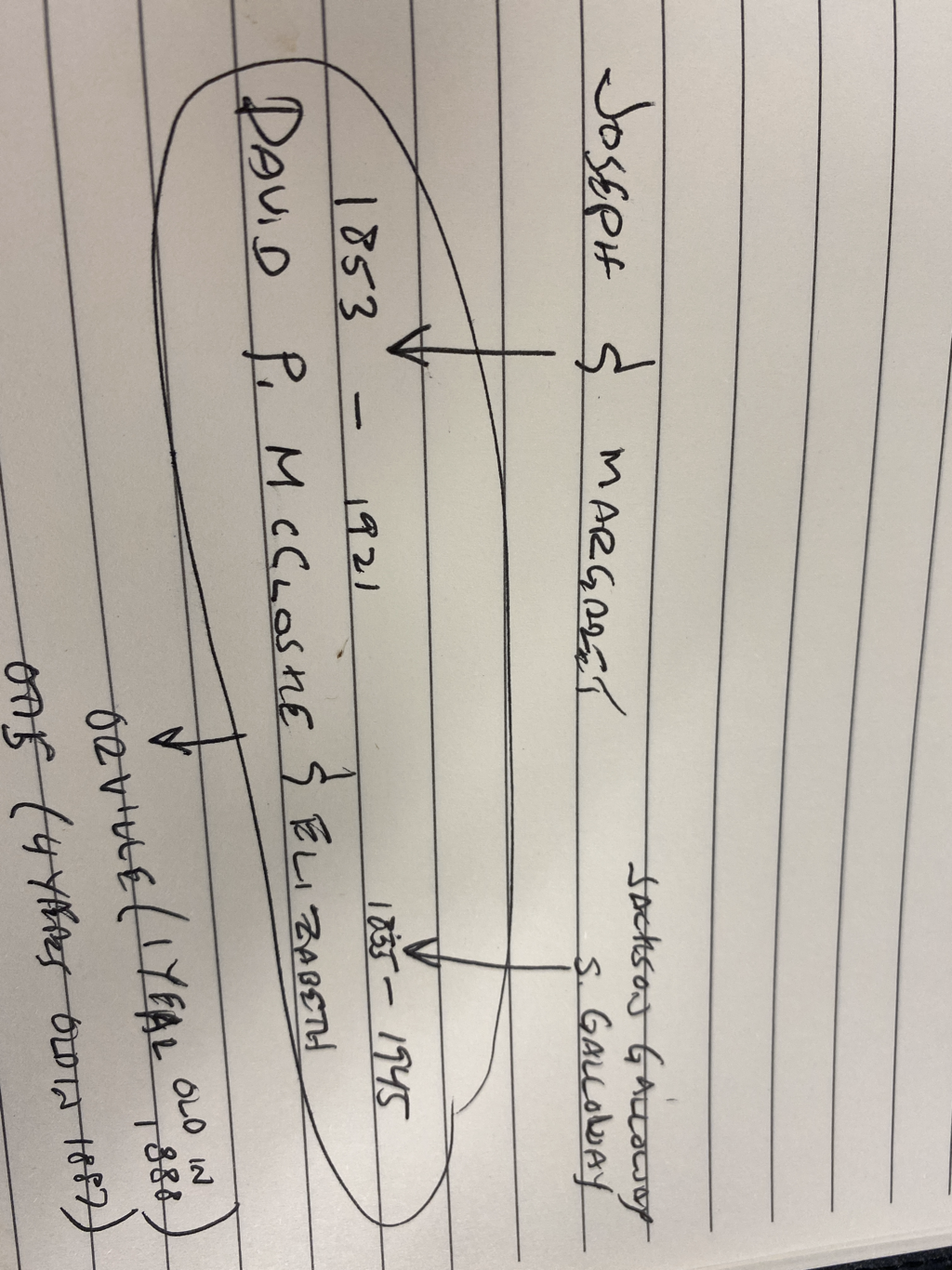

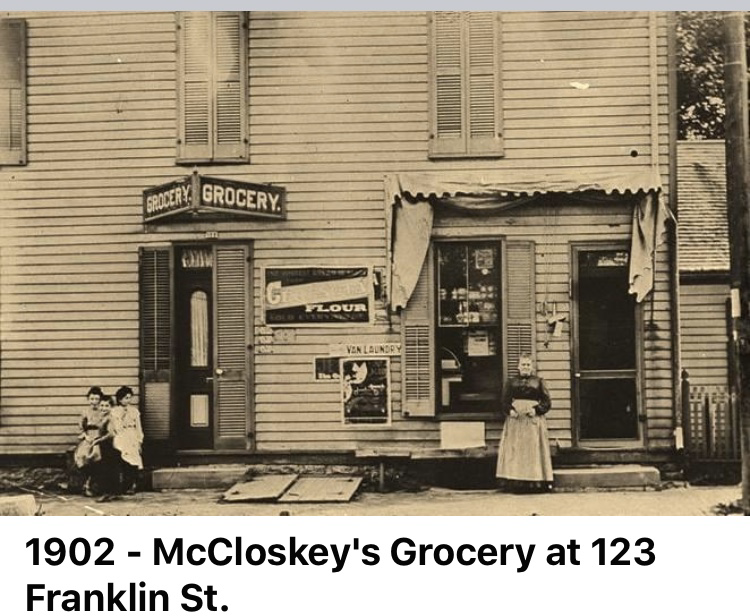

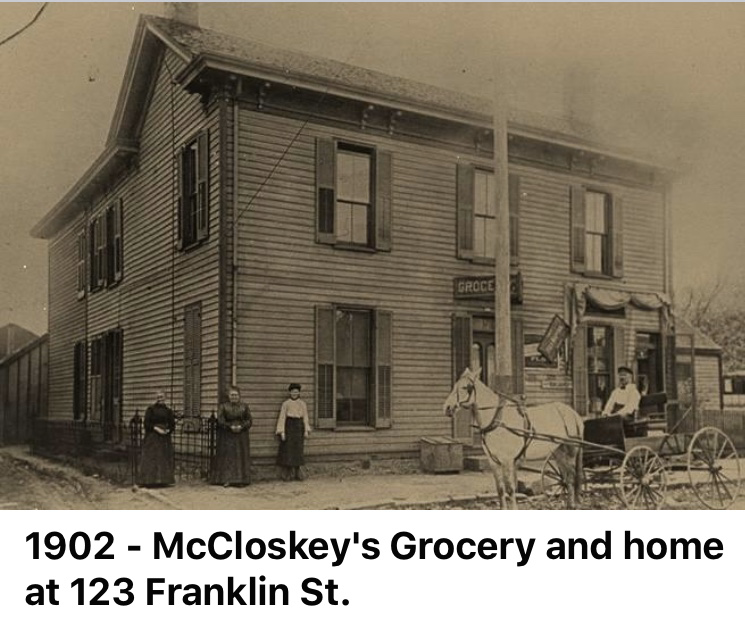

Robert McCloskeys Great Uncle David